READING

Section1

Q Are the results of probability theory always intuitively logical?

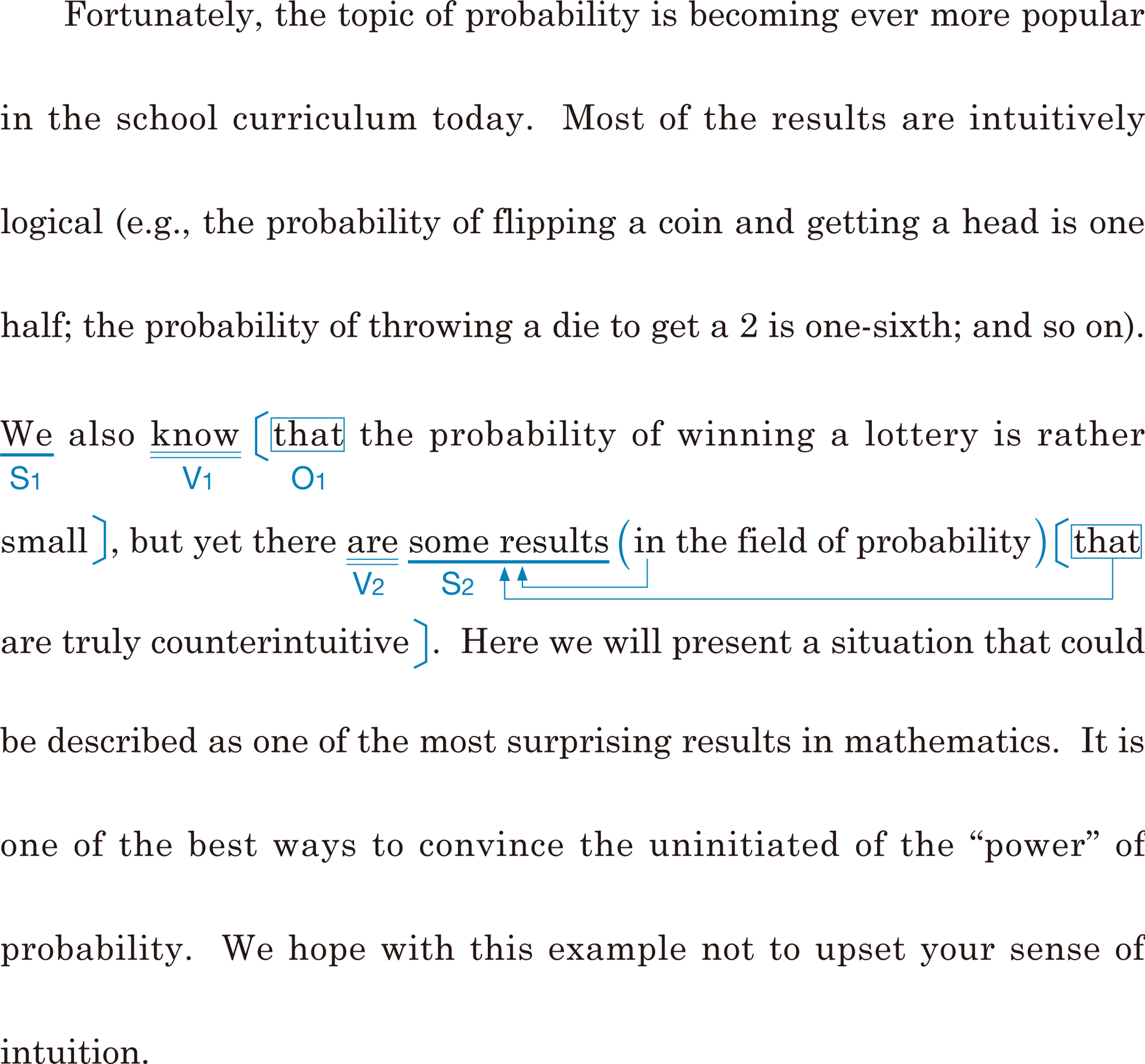

Fortunately, the topic of probability is becoming ever more popular in the school curriculum today. Most of the results are intuitively logical (e.g., the probability of flipping a coin and getting a head is one half; the probability of throwing a die to get a 2 is one-sixth; and so on). We also know that the probability of winning a lottery is rather small, but yet there are some results in the field of probability that are truly counterintuitive. Here we will present a situation that could be described as one of the most surprising results in mathematics. It is one of the best ways to convince the uninitiated of the “power” of probability. We hope with this example not to upset your sense of intuition.

幸いにも,今日確率の話題は学校のカリキュラムにおいて,さらにいっそう人気が出てきています。その結果のほとんどは直観的に理にかなっています(例えば,コインを投げて表が出る確率は 2 分の 1,サイコロを投げて 2 の目が出る確率は 6 分の 1,など)。私たちは宝くじに当たる確率がかなり低いことも知っていますが,それでも確率の分野においては実に反直観的な結果もあります。ここで,数学において最も驚くべき結果の 1 つとして述べられる状況を提示しましょう。これは初心者に確率の「力」を納得させる最もよい方法の 1 つです。この例であなたの直観力が乱されないことを願います。

- probability

- curriculum

- intuitively

- e.g.

- flip(ping)

- die

- counterintuitive

- convince

- uninitiated

- intuition

Section 1 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(1) The topic of probability has recently become less popular in the school curriculum.[F]

(2) The probability of throwing a die to get a 2 is one-sixth.[T]

Section2

Q What is the probability that two of thirty-five people have the same birth date?

Let us suppose you are in a room with about

thirty-five people. What do you think the chances are (or the probability is)

that two of these people have the same birth date (month and day only)? Intuitively,

you usually begin to think about the likelihood of 2 people having the same date out of a selection of 365

days (assuming no leap year). Perhaps 2 out of 365? That

would be a probability of %. A

minuscule chance.

Let’s consider the “randomly” selected group of the first thirty-five presidents of the United States. You may be astonished that there are two with the same birth date: the eleventh president, James K. Polk (November 2, 1795), and the twenty-ninth president, Warren G. Harding (November 2, 1865).

You may be surprised to learn that for a

group of thirty-five, the probability that two members will have the same birth date is greater than 8 out of

10, or =80%.

If you have the opportunity, you may wish to try your own experiment by selecting ten groups of about thirty-five members to check on date matches. For groups of thirty, the probability that there will be a match is greater than 7 out of 10, or, in other words, in 7 of these 10 groups there ought to be a match of birth dates. What causes this incredible and unanticipated result? Can this be true? It seems to be counterintuitive.

あなたは約 35 人の人々と一緒に 1 つの部屋にいると仮定しましょう。そのうちの 2 人が同じ誕生日(月と日のみ)である可能性(あるいは確率)はどれくらいだと思いますか。直観的に,365 日(うるう年は考えないで)という選択の範囲から 2 人が同じ日である可能性についてふつうは考え始めます。たぶん 365 分の 2 では? それだと 2/365 = 0.005479…,すなわち約 0.5%という確率になるでしょう。極めて小さい可能性です。

アメリカ合衆国の初代からの 35 人の大統領という「無作為に」選ばれた集団を検討してみましょう。同じ誕生日の 2 人がいることにあなたは驚くかもしれません。第 11 代大統領のジェームズ・K・ポーク(1795 年 11 月 2 日生まれ)と第 29 代大統領のウォレン・G・ハーディング(1865 年 11 月 2 日生まれ)です。

35 人の集団で 2 人のメンバーが同じ誕生日である確率は 10 分の 8,すなわち 8/10 = 80%より大きいということを知ったらあなたは驚くでしょう。

機会があれば,日付の一致を調べるために約 35 人のメンバーから成る 10 の集団を選んで自分で実験してみたいと思うかもしれませんね。30 人の集団では,一致する可能性は 10 分の 7 より大きいのです。つまり,言い換えれば,これらの 10 の集団のうち 7 つで誕生日の一致があるはずなのです。この信じがたい予想外の結果は何によるものでしょうか。これは本当なのでしょうか。それは直観とは相容れないように思えます。

- birth

- likelihood

- leap

- leap year

- minuscule

- randomly

- astonish(ed)

- Polk

- Warren

- Harding

- experiment

- incredible

- unanticipated

Section2 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(1) The probability that two of a random group of thirty-five people will have the same birth date is less than 1%.[F]

(2) Of the first thirty-five presidents of the United States, there are two who have the same birth date.[T]

Section3

Q What should the amazing demonstration using birth dates and death dates serve as?

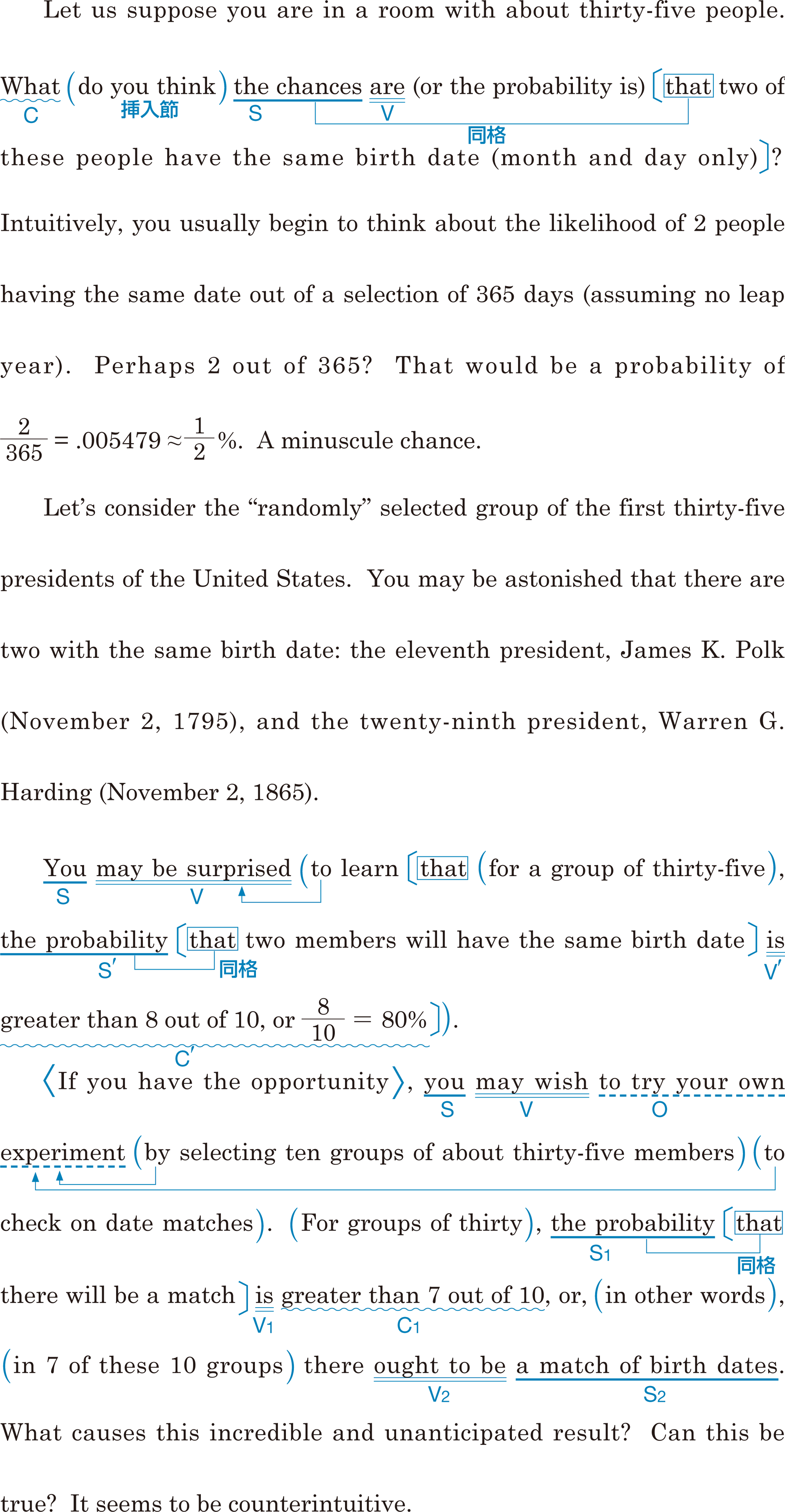

To relieve you of your curiosity, we will

investigate the situation mathematically. Let’s consider a class of thirty-five

students. What do you think is the probability that one selected student

matches his own birth date? Clearly certainty, or 1. This

can be written as .

The probability that another student does not

match the first student is .

The probability that a third student does not

match the first and second students is .

The probability of all thirty-five students

not having the same birth date is the product of these probabilities: .

Since the probability (q) that two students in the group have the same birth date and the probability (p) that two students in the group do not have the same birth date is a certainty, the sum of those probabilities must be 1. Thus, p+q=1.

In this case, In other words, the probability that there will

be a birth date match in a randomly selected group of thirty-five people is somewhat greater than

. This is quite unexpected when you consider that there were

365 dates from which to choose. If you are feeling motivated, you may want to

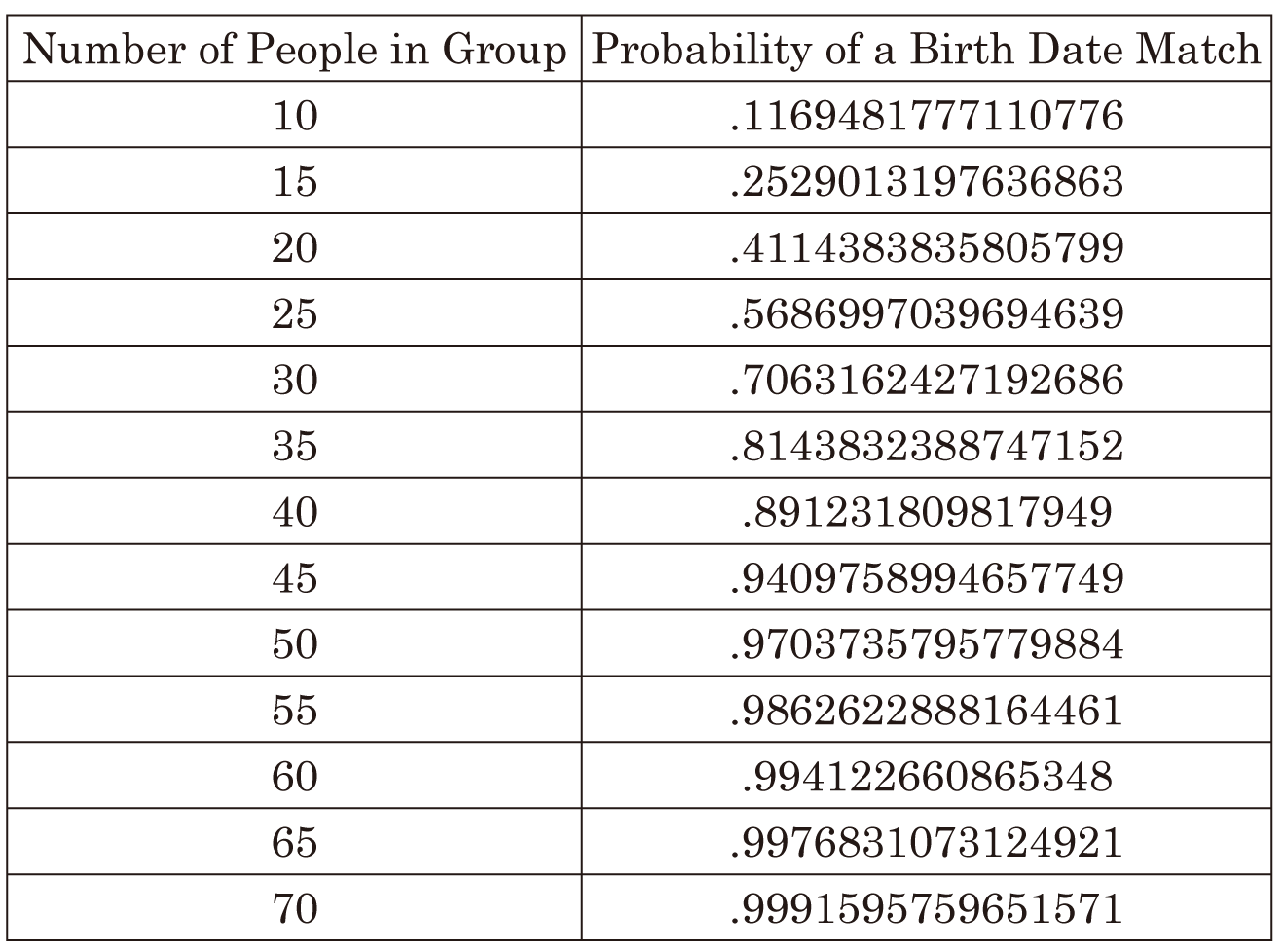

investigate the nature of the probability function. Here are a few values to

serve as a guide:

あなたを好奇心から解放するために,状況を数学的に調べてみましょう。35 人の生徒から成るクラスを考えてみましょう。1 人の選ばれた生徒が自分自身の誕生日と一致する確率はいくつだと思いますか。明らかに「確実」,すなわち 1 です。これは 365/365 と書くことができます。

別の生徒が最初の生徒に一致「しない」確率は (365-1)/365 = 364/365 です。

3 人目の生徒が最初の生徒と 2 人目の生徒に一致「しない」確率は(365-2)/365 = 363/365 です。

35 人の生徒すべてが同じ誕生日で「ない」確率はこれらの確率の積,すなわち,p = 365/365 × (365-1)/365 × (365-2)/365 ×…× (365-34)/365 です。

集団内の 2 人の生徒が同じ誕生日「である」確率(q)と集団内の 2 人の生徒が同じ誕生日「ではない」確率(p)を足せば確実なものなので,これらの確率の総和は 1 にならなくてはなりません。従って,p + q = 1 です。

この場合,q = 1-{365/365 × (365-1)/365 × (365-2)/365 ×…× (365-33)/365 × (365-34)/365} すなわちおよそ 0.8143832388747152 となります。

言い換えれば,無作為に選ばれた 35 人の集団内で誕生日の一致がある確率は 8/10 よりいくぶん大きいのです。選択肢が 365 日あったことを考えると,これはかなり予想外です。もしやる気が出てきたら,その確率(と人数)の関係の性質を調べたいと思うかもしれませんね。指針となる値を以下に少し挙げます。

Notice how quickly “almost-certainty” is reached. With about 55 students in a room the chart indicates that it is almost certain (.99) that two students will have the same birth date.

Were you to do this with the death dates of the first thirty-five presidents, you would notice that two died on March 8 (Millard Fillmore in 1874 and William H. Taft in 1930) and three presidents died on July 4 (John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in 1826, and James Monroe in 1831). This latter case leads some people to argue that you could possibly will your own date of death, since these three presidents died on the most revered day in American history! Above all, this astonishing demonstration should serve as an eye-opener about the inadvisability of relying too much on your intuition.

いかに速く「ほぼ確実」に到達するかに注目して下さい。1 部屋におよそ 55 人の生徒がいれば,2 人の生徒が同じ誕生日であるのはほぼ確実(99%)であることをこの表は示しています。

これを初代からの 35 人の大統領の死亡日で行うと,2 人が 3 月 8 日(ミラード・フィルモアが 1874 年,ウィリアム・H・タフトが 1930 年)に死亡し,3 人の大統領が 7 月 4 日(ジョン・アダムズとトーマス・ジェファーソンが 1826 年,ジェームズ・モンローが 1831 年)に亡くなっていることに気づくでしょう。後者の事例によって,ひょっとすると自分の死亡日を自分で決められたと主張するような人が出てきます。というのも,これらの 3 人の大統領はアメリカの歴史上最も崇められている日に亡くなったからです! 何よりも,この驚くべき証明は,直観に頼りすぎることの不利益に関して目を開かせるものとして役立つはずです。

- relieve

- mathematically

- certainty

- thus

- motivated

- function

- indicate(s)

- Millard

- Fillmore

- William

- Taft

- Adams

- Jefferson

- Monroe

- possibly

- will

- revere(d)

- above all

- astonishing

- eye-opener

- inadvisability

- rely

Section3 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(1) When there are fifty-five students in a room, it is almost certain that two of the students will have the same birth date.[T]

(2) Of the first thirty-five American presidents, no two died on the same date.[F]

Section4

Q What would many people think intuitively about the second decision in the game?

While the previous unit showed us that some probability results are quite counterintuitive, here we will show a very controversial issue in probability that also challenges our intuition. There is a rather famous problem in the field of probability that is typically not mentioned in the school curriculum, yet it has been very strongly popularized in newspapers, magazines and even has at least one book entirely devoted to the subject. It is one of these counterintuitive examples that gives a deeper meaning to understanding the concept of probability.

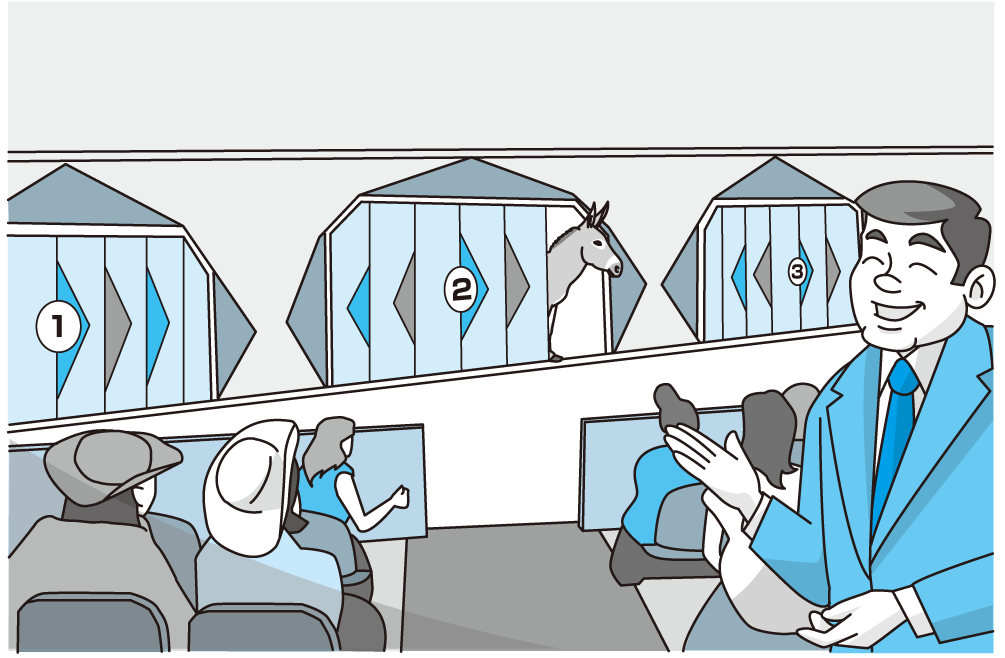

This example stems from the long-running television game show Let’s Make a Deal, which featured a rather curious problematic situation. Let’s look at the game show in a simplified fashion. As part of the game show, a randomly selected audience member would come on stage and be presented with three doors. She was asked to select one, with the hope of selecting the door that had a car behind it, and not one of the other two doors, each of which had a donkey behind it. Selecting the door with the car allowed the contestant to win the car. There was, however, an extra feature in this selection process. After the contestant made her initial selection, the host, Monty Hall, exposed one of the two donkeys, which was behind a not-selected door —— leaving two doors still unopened, the door chosen by the contestant and one other door. The audience participant was asked if she wanted to stay with her original selection (not yet revealed) or switch to the other unopened door. At this point, to heighten the suspense, the rest of the audience would shout out “stay” or “switch” with seemingly equal frequency.

The question is, what to do? Does it make a difference? If so, which is the better strategy to use here (i.e., which offers the greater probability of winning)? Intuitively, most would say that it doesn’t make any difference, since there are two doors still unopened, one of which conceals a car and the other a donkey. Therefore, many folks would assume there is a 50/50 chance that the door the contestant initially selected is just as likely to have the car behind it as the other unopened door.

前章で,確率の結果には実に反直観的なものがあることがわかりましたが,ここでは,また私たちの直観を試す,活発に議論の的になる確率の問題をお見せしましょう。学校のカリキュラムでは通常はふれられない,確率の分野ではかなり有名な問題があります。しかしそれは新聞や雑誌で非常に広く知られており,もっぱらそのテーマを扱った本が少なくとも 1 冊はあるほどです。それは確率の概念の理解により深い意味を与える,この反直観的な事例というものの 1 つです。

この例は Let’s Make a Deal という長年続いていたテレビのゲーム番組が発端です。この番組はかなり興味深くやっかいな状況を呼び物にしていました。このゲーム番組を単純化して見てみましょう。このゲーム番組の中で,無作為に選ばれた 1 人の観客がステージに上がり,3 つの扉を示されます。彼女は,それぞれの後ろにロバがいる 2 つの扉のうちの 1 つではなく,後ろに車がある扉を選ぶことを目指して,1 つを選ぶよう求められます。車がある扉を選ぶと,出場者はその車を獲得することができるのです。しかし,この選択の過程にはさらに見どころがあります。出場者が最初の選択をすると,司会者のモンティ・ホールは,選ばれなかった扉の後ろにいた,2 匹のロバのうちの 1 匹を見せます。この時 2 つの扉,すなわち出場者が選んだ扉ともう 1 つの扉は依然として閉じたままにしておきます。その観客の参加者は,(まだ明らかにされていない)最初の選択のままでいたいか,あるいはもう 1 つの開けられていない扉に変えたいか尋ねられます。この時点で,精神状態のゆらぎをあおるために,残りの観客は「そのままでいろ」あるいは「変えろ」と互角の量で聞こえるように叫ぶのです。

問題は,どうすべきかです。違いが生じるのでしょうか。もしそうなら,ここで使うべきよりよい戦略はどちらでしょうか。(つまり,どちらがより高い勝率を提供するでしょうか。)たいていの人は,直観的に,何の違いも生じないと言うでしょう。なぜなら,2 つの扉は依然として閉じたままで,1 つは車,もう 1 つはロバを隠しているからです。だから多くの人は,出場者が最初に選んだ扉の後ろに車がある確率は,もう一方の開いていない扉とちょうど同じ,という五分五分の可能性があると考えるでしょう。

- unit

- controversial

- issue

- typically

- strongly

- popularize(d)

- entirely

- devote(d)

- stem(s)

- long-running

- problematic

- simplify, simplified

- donkey

- contestant

- extra

- initial

- Monty

- expose(d)

- unopened

- participant

- heighten

- suspense

- seemingly

- frequency

- i.e.

- conceal(s)

- initially

Section4 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) A probability problem from a TV game show has become very popular.[T]

(2) The contestant has only one chance to select a door and can’t change her mind.[F]

(3) The audience of the game show must be silent to allow the contestant to think clearly.[F]

Section5

Q Which is the logical decision, the contestant’s first-choice door or the other unopened door?

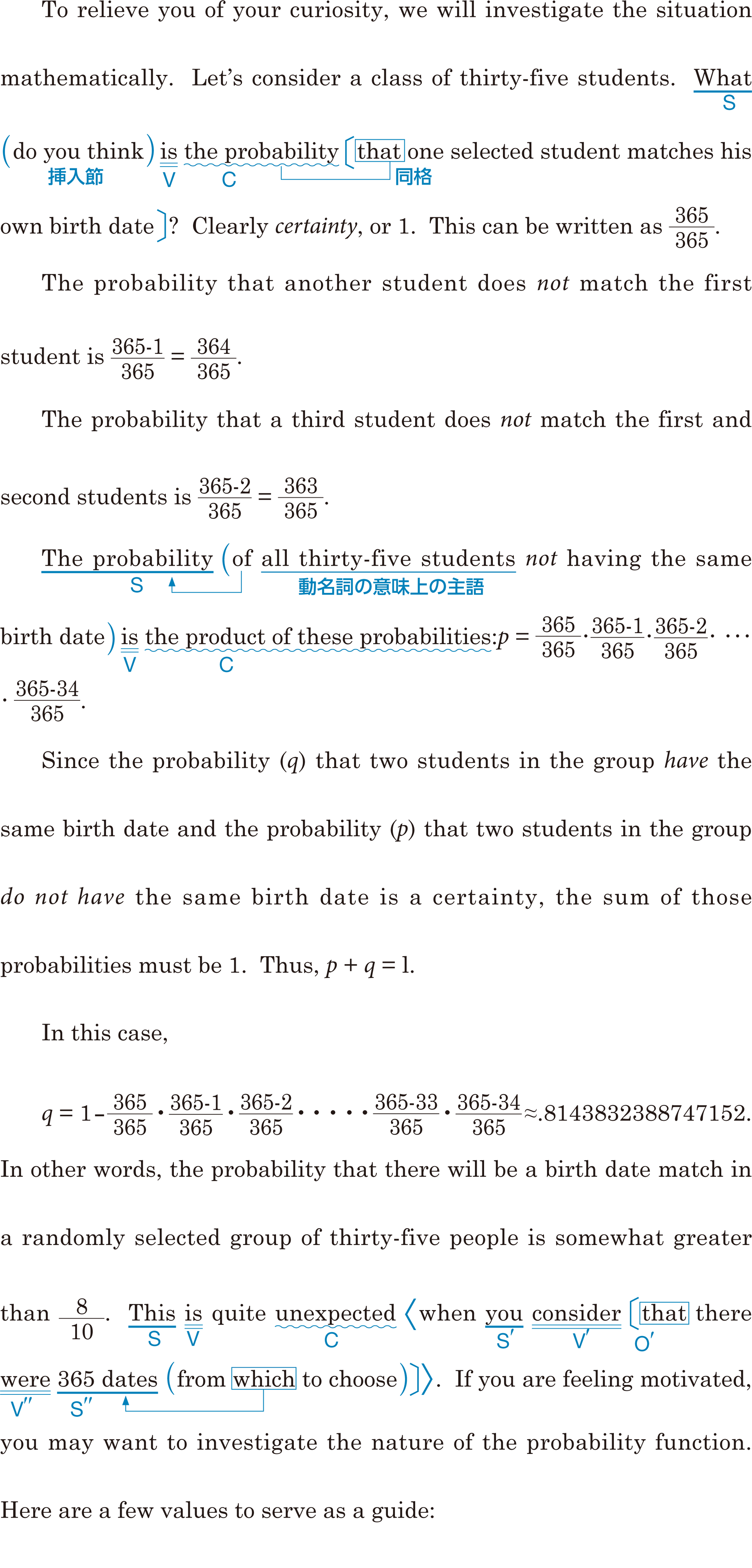

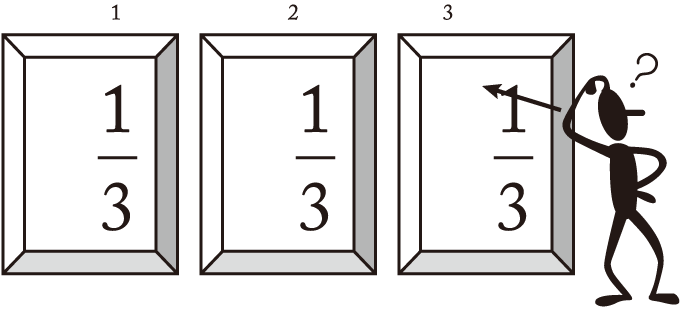

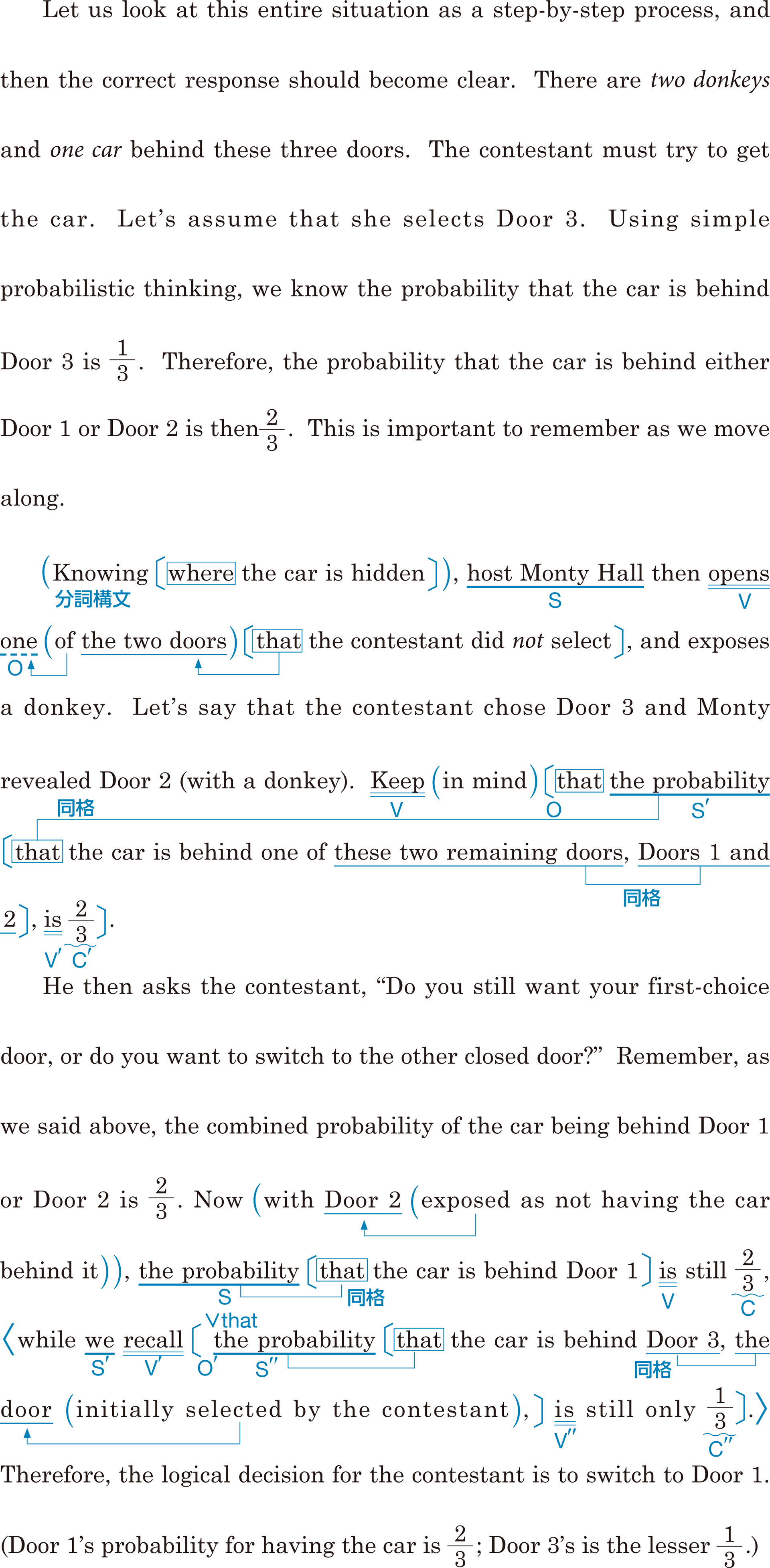

Let us look at this entire situation as a

step-by-step process, and then the correct response should become clear. There

are two donkeys and one car behind these three doors. The

contestant must try to get the car. Let’s assume that she selects Door 3. Using

simple probabilistic thinking, we know the probability that the car is behind Door 3 is . Therefore, the probability that the car is behind either

Door 1 or Door 2 is then

. This

is important to remember as we move along.

この全体の状況を段階的なプロセスとして見てみましょう。すると,正しい答えが明らかになるはずです。これら 3 つの扉の後ろには「2 匹のロバ」と「1 台の車」があります。出場者は車を獲得しようとするにちがいありません。彼女が扉 3 を選ぶとしましょう。簡単な確率的思考を使えば,扉 3 の後ろに車がある確率は 3 分の 1 だとわかります。だからそういうわけで,車が扉 1 か扉 2 の後ろにある確率は 3 分の 2 です。これは先に進むにあたって覚えておかなくてはならない重要なことです。

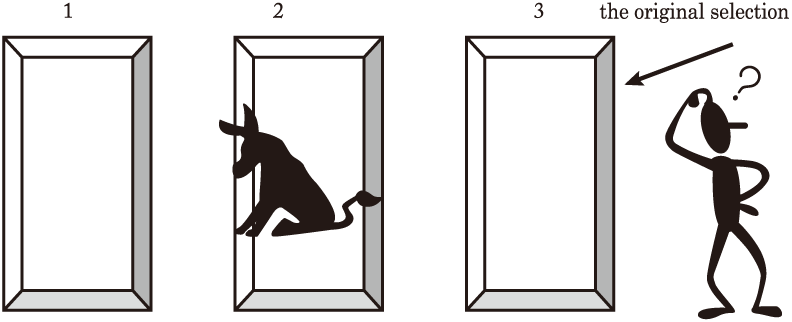

Knowing where the car is hidden, host Monty

Hall then opens one of the two doors that the contestant did not select, and exposes a donkey. Let’s say that the contestant chose Door 3 and Monty revealed Door 2 (with a donkey). Keep in mind that the probability that the car is behind one of these two remaining doors,

Doors 1 and 2, is .

車がどこに隠されているか知っている状態で,司会者のモンティ・ホールは,出場者が選ば「なかった」2 つの扉のうちの 1 つを開けてロバを見せます。例えば,出場者が扉 3 を選び,モンティが(ロバのいる)扉 2 を開けて見せたとしましょう。車がこの残り 2 つの扉,すなわち扉 1 と扉 2 のうちの 1 つの後ろにある確率は,3 分の 2 であることを覚えておいて下さい。

He then asks the contestant, “Do you still

want your first-choice door, or do you want to switch to the other closed door?” Remember,

as we said above, the combined probability of the car being behind Door 1 or Door 2 is . Now with Door 2 exposed as not having the car behind it,

the probability that the car is behind Door 1 is still

,

while we recall the probability that the car is behind Door 3, the door initially selected by the contestant,

is still only

. Therefore,

the logical decision for the contestant is to switch to Door 1. (Door 1’s

probability for having the car is

; Door 3’s is the

lesser

.)

それから,彼は出場者に「最初に選んだ扉のままにしたいですか,それとももう 1 つの閉まっている扉に変えたいですか」と尋ねます。いいですか,前述のように,車が扉 1 か扉 2 の後ろにある合計の確率は 3 分の 2 ですよ。今しがた,扉 2 には後ろに車がないことが明らかになっているので,扉 1 の後ろに車がある確率は依然として 3 分の 2 です。一方で,扉 3 ,すなわち出場者によって最初に選ばれた扉の後ろに車がある確率は,依然として 3 分の 1 しかないことを覚えていますね。したがって,出場者にとって理にかなった決断は,扉 1 に変えることなのです。(扉 1 に車がある確率は 3 分の 2,扉 3 に車がある確率はそれより少ない 3 分の 1 です。)

- entire

- step-by-step

- probabilistic

- move along

- remaining

- first-choice

- combined

- recall

- lesser

Section5 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(1) After the host opens one door, the probability that the car is behind the two doors that were not the contestant’s first choice is still 2/3.[T]

(2) No one knows whether the logical decision is for the contestant to change her choice of door.[F]

Section6

Q What suggestion does the author make by introducing this problem?

This problem has caused many an argument in academic circles, and it was also a topic of discussion in the New York Times, as well as other popular publications.

Although this is a very entertaining and popular problem, it is extremely important to understand the message herewith imparted; and it is one that by all means should have been a part of the school curriculum to make probability not only more understandable but also more enjoyable.

この問題は学界でも多くの論争を巻き起こし,広く普及した他の刊行物などと同様に,ニューヨークタイムズ紙でも議論のトピックとなりました。

これは非常におもしろくて人気のある問題ですが,ここに付与されたメッセージを理解することは極めて重要です。そして,確率をより理解しやすくするだけでなくより楽しいものにするために,絶対に学校のカリキュラムに含まれるべきであったものなのです。

- discussion

- the New York

- publication(s)

- entertaining

- herewith

- impart(ed)

- by all means

- understandable

- enjoyable

Section6 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(1) This problem has attracted plenty of attention in academic circles.[T]

(2) The author thinks that this problem will make probability theory more enjoyable.[T]