READING

Section1

Q What did the author notice while she was living in the United States?

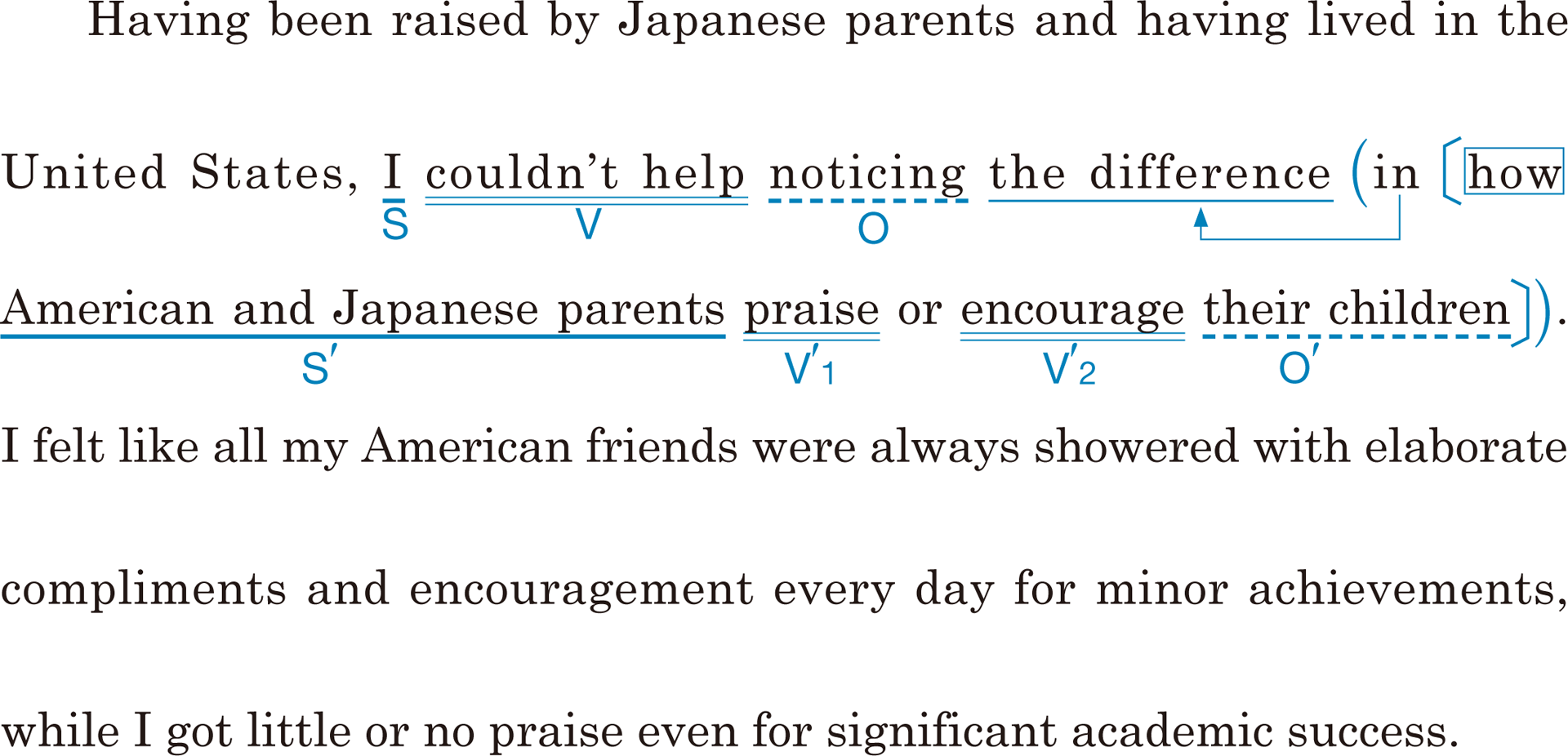

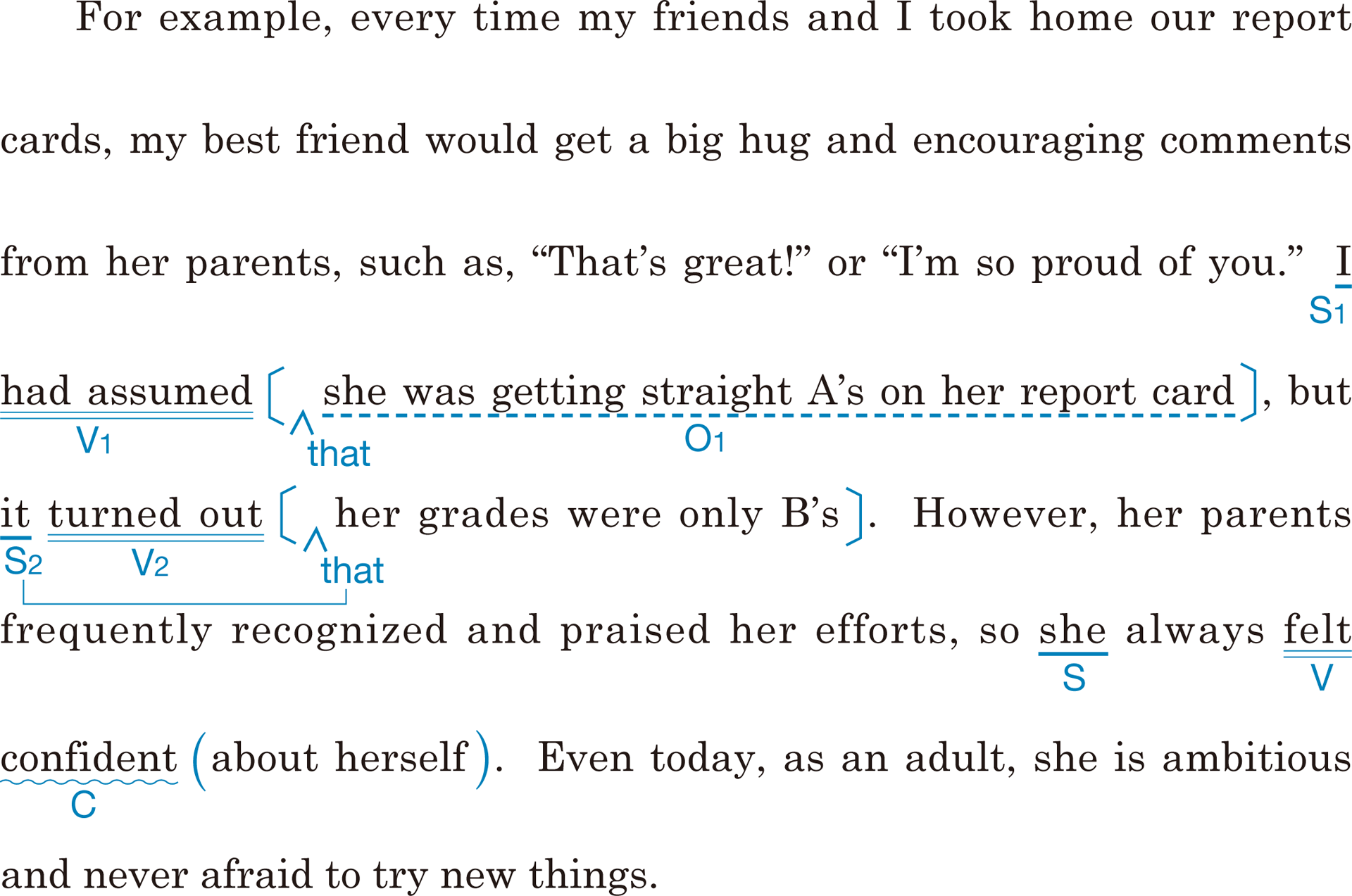

Having been raised by Japanese parents and having lived in the United States, I couldn’t help noticing the difference in how American and Japanese parents praise or encourage their children. I felt like all my American friends were always showered with elaborate compliments and encouragement every day for minor achievements, while I got little or no praise even for significant academic success.

日本人である両親に育てられ,アメリカ合衆国に住んでいたので,私はアメリカ人と日本人の親たちが彼らの子どもたちをほめたり,あるいは励ましたりするやり方の違いに気づかずにはいられませんでした。私は,自分のアメリカ人の友だちは皆,たいしたことのない成績に対して,毎日仰々しいほめ言葉や励ましをいつも惜しみなく与えられているのに,一方で自分はたとえかなり学業成績がよくても,賞賛を得るのはほとんど,あるいはまったくないような気がしていました。

- cannot help …ing

- elaborate

- compliment(s)

- encouragement

- minor

- academic

Section 1 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(1) The author noticed a difference between American and Japanese ways of encouragement because she was raised by American and Japanese parents.[F]

(2) The author’s parents gave her a lot of compliments for her academic achievements.[F]

Section2

Q How did the author’s friend’s parents respond to her report card?

For example, every time my friends and I took home our report cards, my best friend would get a big hug and encouraging comments from her parents, such as, “That’s great!” or “I’m so proud of you.” I had assumed she was getting straight A’s on her report card, but it turned out her grades were only B’s. However, her parents frequently recognized and praised her efforts, so she always felt confident about herself. Even today, as an adult, she is ambitious and never afraid to try new things.

例えば,私の友だちや私が成績表を家に持って帰るたびに,私の親友はぎゅっと抱きしめてもらい,彼女の両親から「すばらしいよ!」あるいは「私はあなたをとても誇りに思うわ。」といった励ましのコメントをもらったものでした。私は彼女が成績表でオール A を取っているのだと思っていましたが,彼女の成績は B ばかりだとわかりました。しかし,彼女の両親がしばしば彼女の努力を認め,ほめたので,彼女はいつも自分自身について自信を持てたのです。大人になった今日でも,彼女は意欲的で,新しいことを試すのを決して恐れることはありません。

- every time

- report card(s)

- hug

- encouraging

- comment(s)

- assume(d)

- turn out

- frequently

- ambitious

Section2 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) One of the author’s American friends was always getting encouraging comments from her parents about her report card.[T]

(2) The author’s American friend was always getting straight A’s on her report card.[F]

(3) Even today, the author’s American friend actively tries new things.[T]

Section3

Q How did the author’s parents respond to her report card?

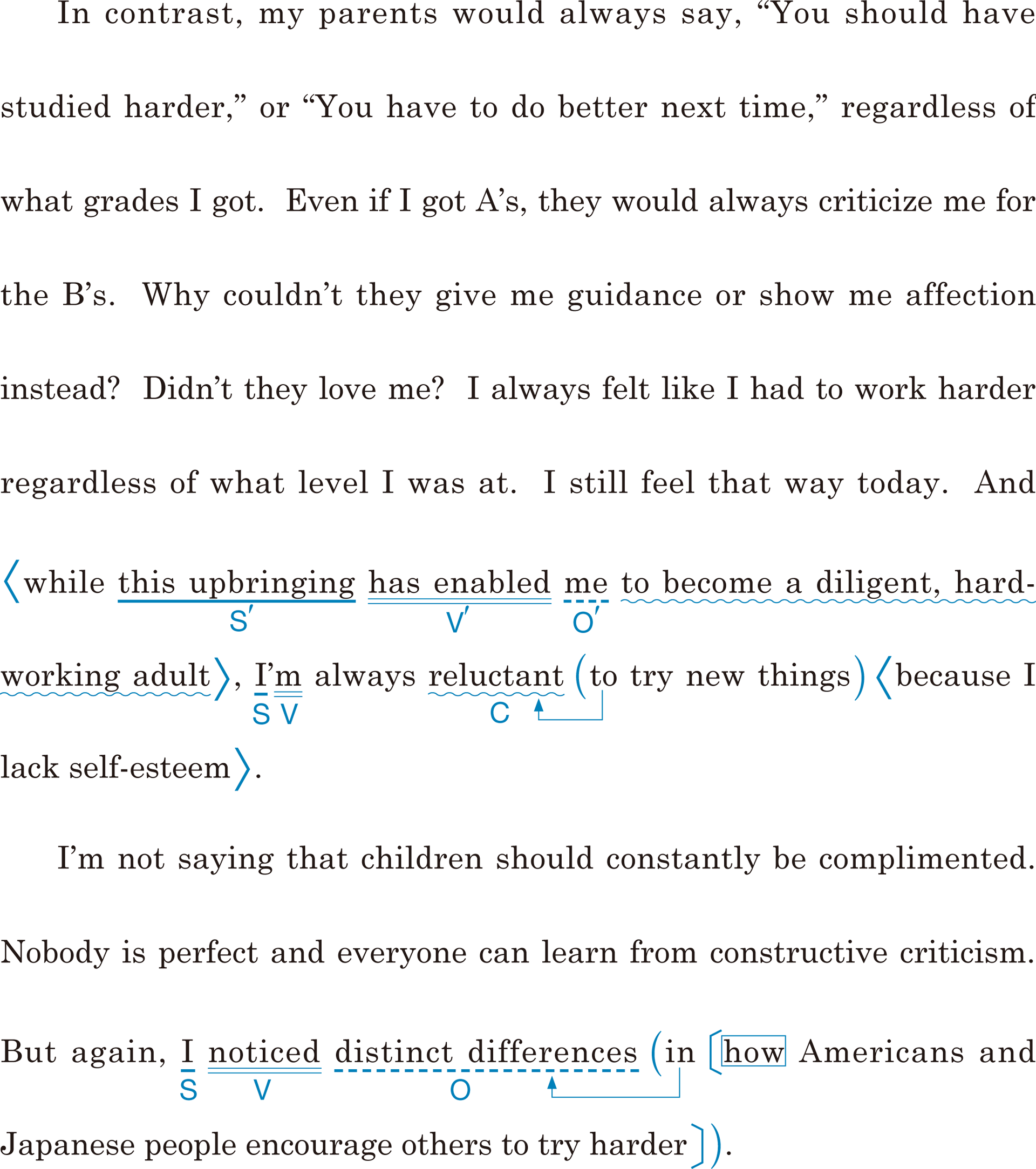

In contrast, my parents would always say, “You should have studied harder,” or “You have to do better next time,” regardless of what grades I got. Even if I got A’s, they would always criticize me for the B’s. Why couldn’t they give me guidance or show me affection instead? Didn’t they love me? I always felt like I had to work harder regardless of what level I was at. I still feel that way today. And while this upbringing has enabled me to become a diligent, hard-working adult, I’m always reluctant to try new things because I lack self-esteem.

I’m not saying that children should constantly be complimented. Nobody is perfect and everyone can learn from constructive criticism. But again, I noticed distinct differences in how Americans and Japanese people encourage others to try harder.

それとは対照的に私の両親は,私がどんな成績を取ったかに関係なく,「おまえはもっと熱心に勉強すべきだったのに」あるいは「あなたは次回はもっとよい結果を出さなければ」といつも言ったものでした。たとえ私が A を取っても,B のことで常に私を批判したのです。彼らはなぜその代わりに私を指導したり,あるいは愛情を示したりすることができなかったのでしょうか? 彼らは私を愛していなかったのでしょうか? 私はいつも,自分がどのレベルにいるかにかかわらず,もっと努力しなければならないように感じていました。私はまだ今日でもそのように感じます。そして,この教育法のおかげで私は勤勉で懸命に働く大人になることができた一方で,自尊心を欠いているために,いつも新しいことを試すことに消極的なのです。

私は子どもたちは絶えずほめられるべきだ,と言っているわけではありません。誰も完璧ではありませんし,誰でも建設的な批評から学ぶことができます。しかしこの場合もまた,アメリカと日本の人々が,もっと熱心にやってみるよう人を励ますやり方のはっきりとした違いに私は気づいたのです。

- contrast

- in contrast

- criticize

- guidance

- affection

- that way

- upbringing

- enable(d)

- diligent

- reluctant

- lack

- self-esteem

- constantly

- constructive

- criticism

Section3 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) The author’s parents would criticize her B grades without praising her A’s.[T]

(2) Now the author feels that thanks to her parents’ guidance, she is always eager to try new things.[F]

(3) The author thinks parents should compliment their children all the time.[F]

Section4

Q How did the author and her friend respond to their parents’ reactions?

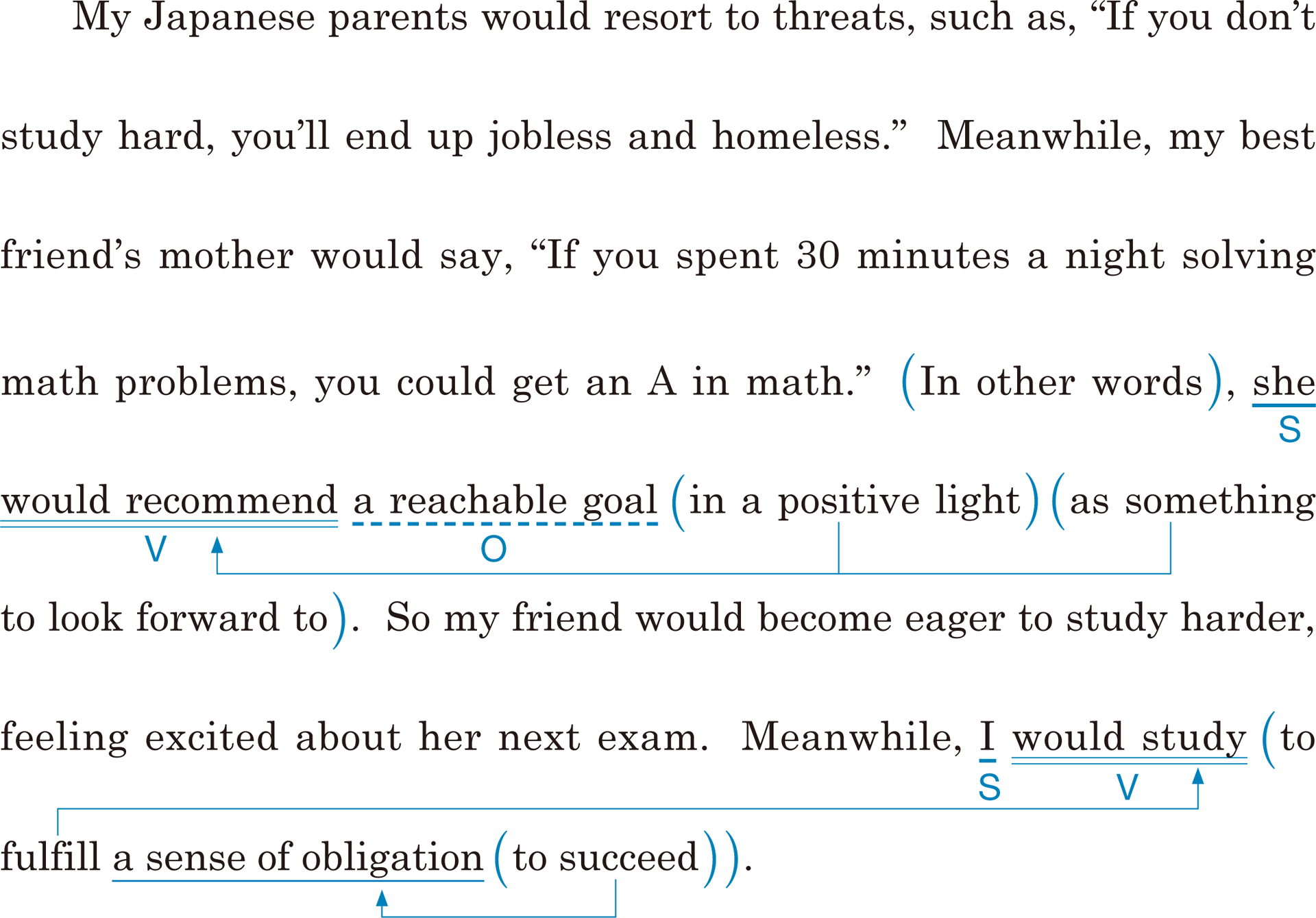

My Japanese parents would resort to threats, such as, “If you don’t study hard, you’ll end up jobless and homeless.” Meanwhile, my best friend’s mother would say, “If you spent 30 minutes a night solving math problems, you could get an A in math.” In other words, she would recommend a reachable goal in a positive light as something to look forward to. So my friend would become eager to study harder, feeling excited about her next exam. Meanwhile, I would study to fulfill a sense of obligation to succeed.

日本人である私の両親は,「熱心に勉強しないなら,結局は職も家も得られないぞ。」などと脅しに訴えたものでした。一方,私の親友の母親は「もしあなたが一晩30分ずつ数学の問題を解くのに費やせば,数学で A を取ることができるわよ。」と言ったものでした。言い換えれば,彼女は前向きな考え方で,楽しみにすることとして,到達可能な目標を勧めていたのです。ですから私の友だちは,次の試験にわくわくしながら,もっと熱心に勉強したいと熱望するようになったものでした。一方で,私は成功しなければならないという義務感を満たすために勉強したものでした。

- resort

- threat(s)

- jobless

- homeless

- meanwhile

- in other words

- reachable

- fulfill

- obligation

Section4 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) The author’s parents never told her directly to study harder.[F]

(2) The author’s friend’s mother would recommend a reachable goal to get her daughter to study harder.[T]

(3) The author never felt a sense of obligation to succeed while she was studying.[F]

Section5

Q What is the main difference between the American and Japanese ways of communi cating with children?

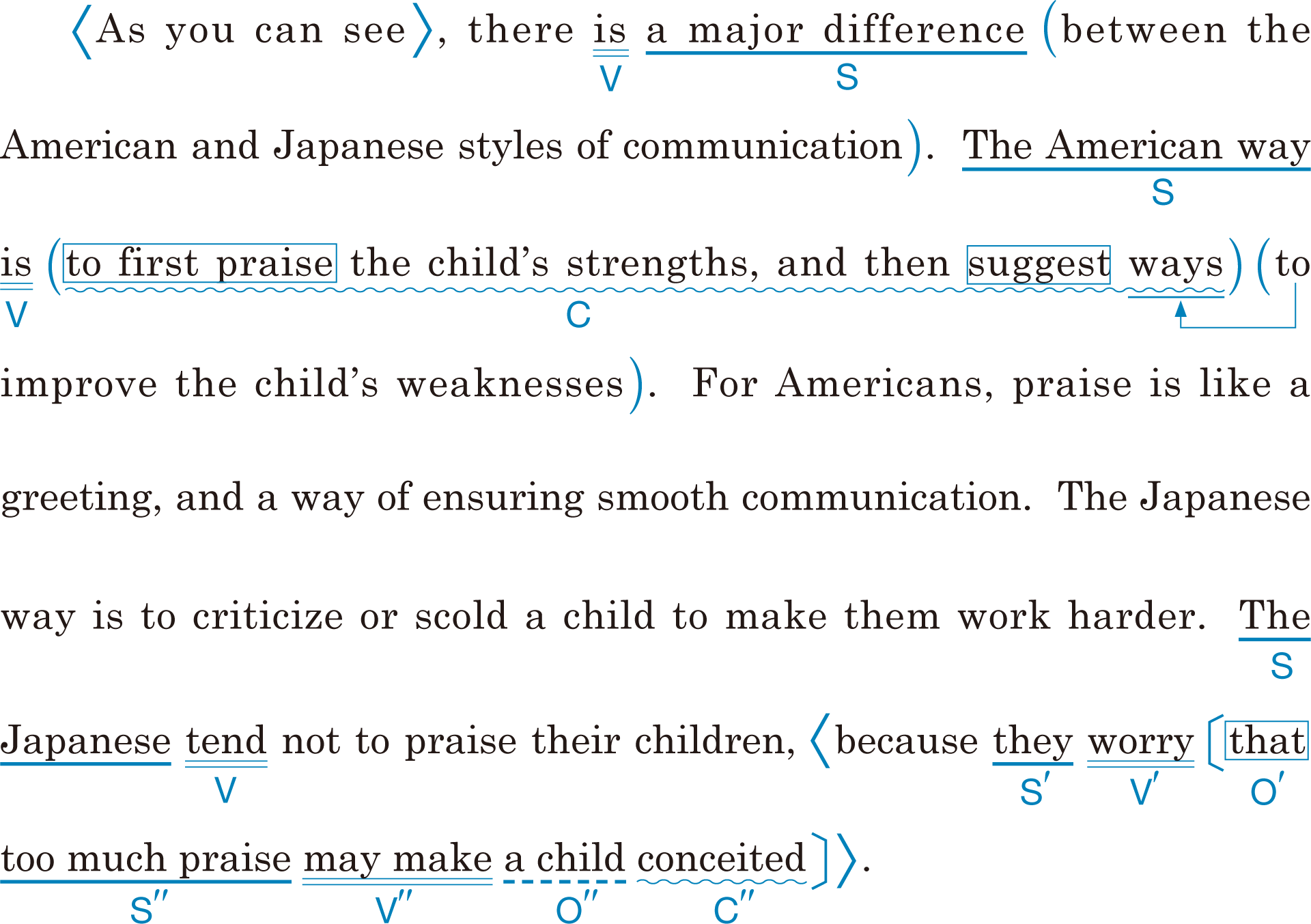

As you can see, there is a major difference between the American and Japanese styles of communication. The American way is to first praise the child’s strengths, and then suggest ways to improve the child’s weaknesses. For Americans, praise is like a greeting, and a way of ensuring smooth communication. The Japanese way is to criticize or scold a child to make them work harder. The Japanese tend not to praise their children, because they worry that too much praise may make a child conceited.

おわかりのように,アメリカ人と日本人の意思疎通のスタイルには,大きな違いがあります。アメリカ人のやり方は,まず子どもの長所をほめて,それから子どもの短所を改善する方法を提案することです。アメリカ人にとってほめることはあいさつのようなものであり,また円滑な意思疎通を確実にする手段なのです。日本人のやり方は,子どもをさらに頑張らせるために批判したり,あるいはしかったりすることです。日本人は彼らの子どもたちをほめない傾向がありますが,それはあまりほめすぎると,子どもをうぬぼれさせるかもしれないと心配するからです。

- improve

- weakness(es)

- ensure, ensuring

- smooth

- conceited

Section5 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) American parents tend to first criticize their children’s weak points and tell them to study much harder.[F]

(2) Among Americans, praise seems to be a way of ensuring smooth communication.[T]

(3) The Japanese don’t praise their children too much because they think the children may become conceited.[T]

Section6

Q What kind of communication style is used for adults in America?

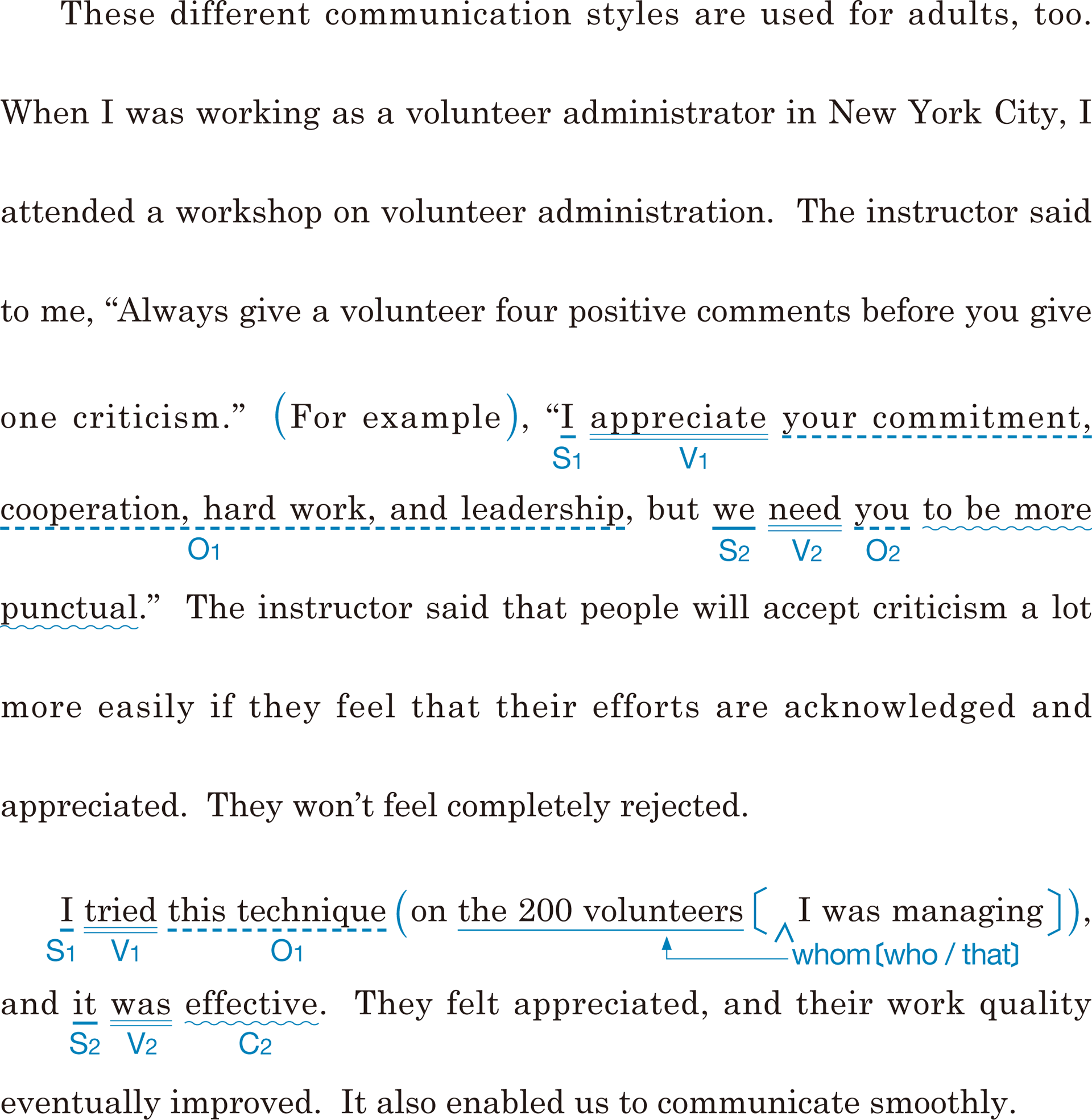

These different communication styles are used for adults, too. When I was working as a volunteer administrator in New York City, I attended a workshop on volunteer administration. The instructor said to me, “Always give a volunteer four positive comments before you give one criticism.” For example, “I appreciate your commitment, cooperation, hard work, and leadership, but we need you to be more punctual.” The instructor said that people will accept criticism a lot more easily if they feel that their efforts are acknowledged and appreciated. They won’t feel completely rejected.

I tried this technique on the 200 volunteers I was managing, and it was effective. They felt appreciated, and their work quality eventually improved. It also enabled us to communicate smoothly.

この異なる意思疎通のスタイルは,大人に対しても用いられます。ボランティアの管理者としてニューヨーク市で働いていた時,私はボランティアの管理に関する研修会に出席しました。講師は私に,「ボランティアにはいつも,1つ批判をする前に4つの肯定的な意見を伝えなさい。」と言いました。例えば,「私はあなたの献身,協力,勤勉さ,そして指導力を評価していますが,もっと時間に正確になってもらう必要があります。」のようにです。講師は,人は自分たちの努力が認められ評価されていると感じると,批判をもっとずっと簡単に受け入れるものだと言いました。(そうすれば)彼らは,完全に拒絶されたようには感じないものなのだと。

私はこのテクニックを,自分が管理していた200名のボランティアに試しましたが,これは効果的でした。彼らは評価されていると感じ,さらに彼らの仕事の質は結局は改善したのです。このテクニックのおかげで私たちは,円滑に意思を通わせ合うこともできました。

- administrator

- workshop

- administration

- instructor

- appreciate

- commitment

- cooperation

- leadership

- punctual

- acknowledge(d)

- technique

- effective

Section6 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) The instructor at the volunteer administration workshop advised the author not to criticize volunteers.[F]

(2) The instructor said that giving some positive comments before criticism would keep people from feeling rejected.[T]

(3) The advice from the author’s instructor helped her communicate more smoothly with volunteer workers.[T]

Section7

Q How did the author feel about the ways her bosses communicated with her in America and Japan?

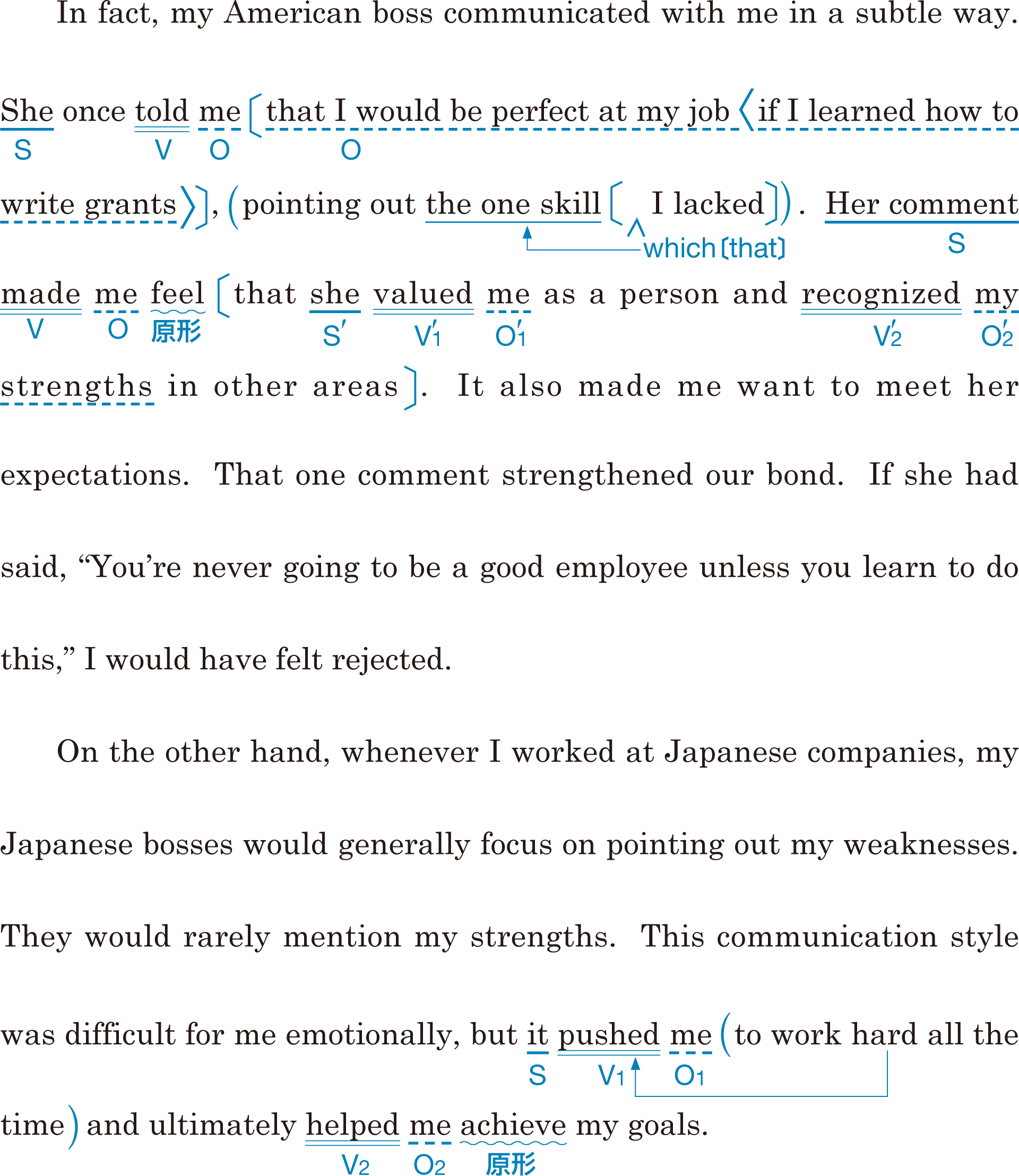

In fact, my American boss communicated with me in a subtle way. She once told me that I would be perfect at my job if I learned how to write grants, pointing out the one skill I lacked. Her comment made me feel that she valued me as a person and recognized my strengths in other areas. It also made me want to meet her expectations. That one comment strengthened our bond. If she had said, “You’re never going to be a good employee unless you learn to do this,” I would have felt rejected.

On the other hand, whenever I worked at Japanese companies, my Japanese bosses would generally focus on pointing out my weaknesses. They would rarely mention my strengths. This communication style was difficult for me emotionally, but it pushed me to work hard all the time and ultimately helped me achieve my goals.

実際,私のアメリカ人の上司は巧みなやり方で私と意思を通じ合いました。彼女はかつて,私に欠けている1つの技術を指摘して,もし譲渡証書の書き方を学んだら,私の仕事は完璧になるだろう,と私に言いました。彼女の意見は,彼女が私を人として尊重し,他の分野では私の長所を認めていると私に感じさせてくれました。それはまた私に,彼女の期待に応えたいと思わせたのです。あの1つの意見が私たちのきずなを強めました。もし彼女が,「あなたは,これを身につけない限り決してよい従業員にはなりませんよ」と言っていたら,私は拒絶されたと感じていたことでしょう。

一方,私が日本の会社で働く時はいつでも,私の日本人の上司たちはたいてい私の短所を指摘することに重点を置いたものでした。彼らが私の長所にふれることはめったにありませんでした。この意思疎通のスタイルは私には感情的には厳しいものでしたが,それが私をいつも努力させたうえ,最終的に私が自分の目標を達成する助けとなったのでした。

- subtle

- grant(s)

- point out

- expectation(s)

- strengthen(ed)

- bond

- employee

- unless

- whenever

- generally

- emotionally

Section 7 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) The comment by the author's American boss made her lose her motivation to work.[F]

(2) The author felt rejected when her American boss advised her to learn how to write grants.[F]

(3) The communication style of the author's Japanese bosses helped her achieve her goals.[T]

Section8

Q According to the author, why is it important to adopt an appropriate style of encouragement for each individual?

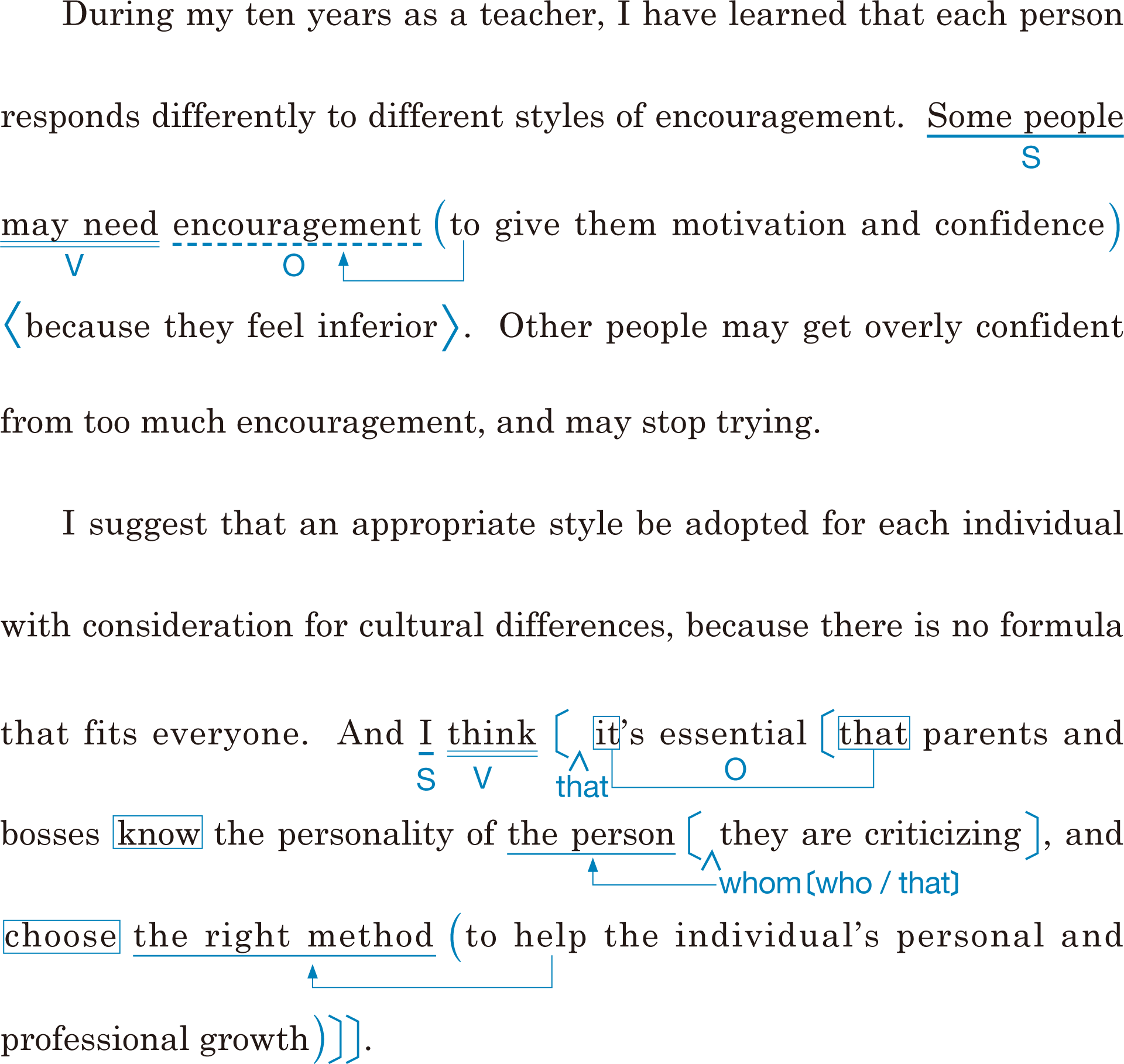

During my ten years as a teacher, I have learned that each person responds differently to different styles of encouragement. Some people may need encouragement to give them motivation and confidence because they feel inferior. Other people may get overly confident from too much encouragement, and may stop trying.

I suggest that an appropriate style be adopted for each individual with consideration for cultural differences, because there is no formula that fits everyone. And I think it’s essential that parents and bosses know the personality of the person they are criticizing, and choose the right method to help the individual’s personal and professional growth.

教師として過ごした10年間に私は,人はそれぞれさまざまなスタイルの励ましに,さまざまな反応をするということを知りました。自分たちが劣っていると感じているために,やる気や自信を与える励ましが必要な人たちがいるかもしれません。過度な励ましから過剰に自信を持って,努力するのをやめる人たちもいるかもしれません。

私は,文化的な違いに配慮しながら,ふさわしいスタイルがそれぞれの個人に対して採られるように提案します。というのも誰にでも合う決まったやり方はないからです。そして,親や上司たちは自分が批判している人の個性を知り,そしてその個人の人間的な,また職業的な成長を助ける正しい方法を選ぶことが,きわめて重要だと考えています。

- respond(s)

- differently

- motivation

- overly

- appropriate

- consideration

- formula

- essential

- personality

- method

- personal

- growth

Section 8 : True or False ?

(1) T / F

(2) T / F

(3) T / F

(1) The author says that some people may stop trying when they get too much encouragement.[T]

(2) The author believes that cultural differences do not need any consideration when encouraging someone.[F]

(3) The author believes that each individual needs a different style of encouragement.[T]