Disucussion Topic

Q1 What is your oldest memory in your life?

Q2 Describe your episode as a child that your family often talk about. Do you remember it?

Section1

Everyone has an earliest memory —— clearly one of our memories must be the oldest. And, barring a belief in past lives, this memory must be of an event that happened within a knowable time frame —— some time between now and when our minds first came into existence. But how can we discern whether the earliest memory we think we have is an accurate representation of something that happened?

When people claim to be able to remember the mobile that hung above their beds when they were a baby, or the hospital room in which they were born, or the warmth they felt inside their mother’s womb, they are recalling what psychologists refer to as impossible memories. Research has long established that as adults we cannot accurately retrieve memories from our infancy and early childhood. To put it simply, the brains of babies are not yet physiologically capable of forming and storing long-term memories. And yet many people seem to have such memories anyway, and are often convinced that they are accurate because they can see no other plausible origin for these recollections.

人は誰でも最初の記憶を持っています。明らかに私たちの記憶の1つは最も古いものであるはずです。また,前世を信じないのであれば,この記憶は認識できる時間枠の範囲内で,つまり今と意識が誕生した時の間のいつかに起こった出来事についての記憶であるはずです。しかし,自分が持っていると思っている最初の記憶が,起こったことを正確に描写しているかどうかを,私たちはどのようにしたら見分けることができるのでしょうか。

人々が,自分が赤ちゃんの時に自分のベッドの上にぶらさがっていたモビールや自分が生まれた病院の部屋,あるいは母親の子宮の中で感じた温かさなどを思い出すことができると主張する時,彼らは心理学者が不可能な(ありえない)記憶とよんでいるものを思い出しているのです。大人になって自分の乳児期や幼児期の記憶を正確に呼び戻すことはできないということは,ずいぶん前から研究によって立証されています。簡単に言えば,赤ちゃんの脳には,長期記憶を形成したり蓄積したりする能力が生理学的にはまだないのです。それでもとにかく,多くの人はそのような記憶を持っているように見え,しばしばそれが正確であるように思い込んでいますが,それはその記憶の起源として他に妥当なものを見つけることができないからです。

Q1 What are impossible memories?

- knowable 知り得る

- come into existence 誕生する

- discern ~を知る

- representation 描写

- claim …であると主張する

- mobile モビール

- hung (< hang ぶら下がる)

- warmth 温かさ

- womb 子宮

- psychologist(s) 心理学者

- accurately 正確に

- retrieve ~を取り戻す

- infancy 乳児期

- physiologically 生理学上の

- capable 才能があって

- be capable of (…する)能力がある

- long-term 長期の

- plausible 妥当な

- recollection(s) 記憶

Section2

But actually, it does not take much to think of a few alternative explanations. Is there really no other way we could know what our mobile or crib looked like, or that we got caught in the latch of our crib, or that we had a musical bear? Surely there could be external sources for this information: perhaps old photographs or a parent’s retelling of events. We might even have memories of objects of personal importance because they were still around much later in our lives.

So we know that at least some of the necessary raw material to build a convincing picture of our earlier childhood can be found elsewhere. When we then place this information into seemingly appropriate contexts, such as a retelling of an early life event, we can unintentionally fill in our memory gaps, and make up details. Our brains piece together information fragments in ways that make sense to us and which can therefore feel like real memories. This is not a conscious decision by the ‘rememberer’, rather something that happens automatically. Two of the main processes during which this occurs are known as confabulation and source confusion.

しかし,実際にはこれを説明する他の理由をいくつか思いつくのは大変なことではありません。モビールやベビーベッドがどのようなものだったかや,ベビーベッドの金具に引っかかってしまったことや,音楽が流れるクマのぬいぐるみを持っていたことを知る他の手段は本当に存在しないのでしょうか。きっと外部にこれらの情報源があるのでしょう。すなわち,おそらく古い写真や,その出来事を親が繰り返し語ることなどです。私たちは個人的に大事な物の記憶を持ってさえいるかもしれませんが,それはそれらが人生のもっとあとの時期になってもまだ周りにあったからです。

ですから,私たちが幼年期の信ぴょう性のある描写を作り上げるために必要な素材の少なくともいくつかが,どこか他の場所で見つかる可能性があるということがわかっています。そこで,私たちがこの情報を,ある幼児期の出来事の思い出話のような,一見すると妥当な場面に組み込むと,私たちは無意識のうちに記憶のすき間を埋め,詳細を創り上げることができるのです。私たちの脳は自分たちにとってつじつまが合うように情報の断片をつなぎ合わせるので,そのためそれらが本当の記憶であるかのように感じられるのです。これは「記憶をしている者」が意識的に判断しているのではなく,むしろ無意識に起きていることなのです。このことが起こっている間の2つの主要なプロセスは,作話と情報源の混乱として知られています。

Q1 What are examples of external sources that convince your memories are plausible?

Q2 How do we unintentionally fill in our memory gaps, and make up details?

- alternative 他の

- crib ベビーベッド

- latch 掛け金

- source(s) (情報などの)出所

- retell ~を繰り返して語る

- elsewhere どこか他の所で〔へ〕

- unintentionally 無意識のうちに

- fill in ~を埋める

- gap(s) すき間

- make up (物語など)を作る

- piece together ~をつなぎ合わせて理解する

- fragment(s) 断片

- make sense 意味を成す

- conscious 意識している

- rememberer 記憶者

- confabulation 作話

Section3

As Louis Nahum and his cognitive neuroscience colleagues at the University of Geneva put it, ‘Confabulation denotes the emergence of memories of experiences and events which never took place.’ This single word describes a complex phenomenon that affects many of our memories, particularly early ones. Of course, in the case of early childhood memories, this definition can fall a bit short: the event may have actually taken place, it is just impossible that our brains were able to store this information at such a young age and present it back to us in a single meaningful memory later on.

Alternatively, the belief that we have early childhood memories of events like birth may be simply due to misidentifying the sources of information. This is known as source confusion —— forgetting the source of information and misattributing it to our own memory or experience. Wanting to remember our lovely childhoods, we may mistake our mother’s stories for our memories. Or we may meld into our personal narratives recollections told to us by our siblings and friends. Or we may mistake our imagination of what our childhood could have been like for a real memory of what it was like. Of course, memory errors can also be due to confabulation and source confusion working in tandem.

ジュネーブ大学のルイ・ナフムと彼の認知神経科学の同僚たちが言うところでは,「作話とは,決して起こらなかった経験や出来事の記憶の出現を意味する」のです。この作話という1つの単語が私たちの記憶,特に早期の記憶の多くに影響する複雑な現象を説明します。もちろん,幼児期の記憶の場合においてはこの定義では少し足りないかもしれません。その出来事が実際に起きたかもしれないとしても,私たちの脳はそのような幼い年齢ではこの情報をしまっておいて,後に1つの意味のある記憶として示し直すことが単に不可能なのです。

あるいは私たちが出生といったような幼年期の出来事の記憶を持っていると信じていることは,単に情報源を誤認しているせいかもしれません。これは情報源の混乱として知られています。すなわち情報源を忘れてしまい,間違ってそれを私たち自身の記憶や経験のものとしてしまうのです。私たちは楽しかった子供時代を覚えておきたいので,母親の話を自分の記憶と取り違えているのかもしれません。あるいは,兄弟や友人が語ってくれた回想を個人的な思い出話に混ぜこんでいるのかもしれません。または,自分の幼年時代はこんな風だったかもしれないという想像と実際にそうであったことの本当の記憶とを取り違えているのかもしれません。もちろん,過誤(虚偽)記憶は作話と情報源の混乱が同時に起きているせいである可能性もあります。

Q1 What is “confabulation”?

Q2 How can “source confusion” occur?

- Louis ルイ

- Nahum ナフム

- neuroscience 神経科学

- Geneva ジュネーブ

- denote(s) ~を意味する

- emergence 出現

- phenomenon 現象

- definition 定義

- fall short 足りない

- later on のちに

- alternatively あるいは

- misidentify(ing) ~を誤認する

- misattribute, misattributing 《misattribute ~ to ...で》誤って~を…のせいにする

- meld 《meld ~ into ...で》~と…を混同する

- narrative(s) 話

- sibling(s) (男女の別なく)きょうだい

- imagination 想像

- error(s) 誤り

- tandem 連携〔相互依存〕関係

- in tandem 同時に

Section4

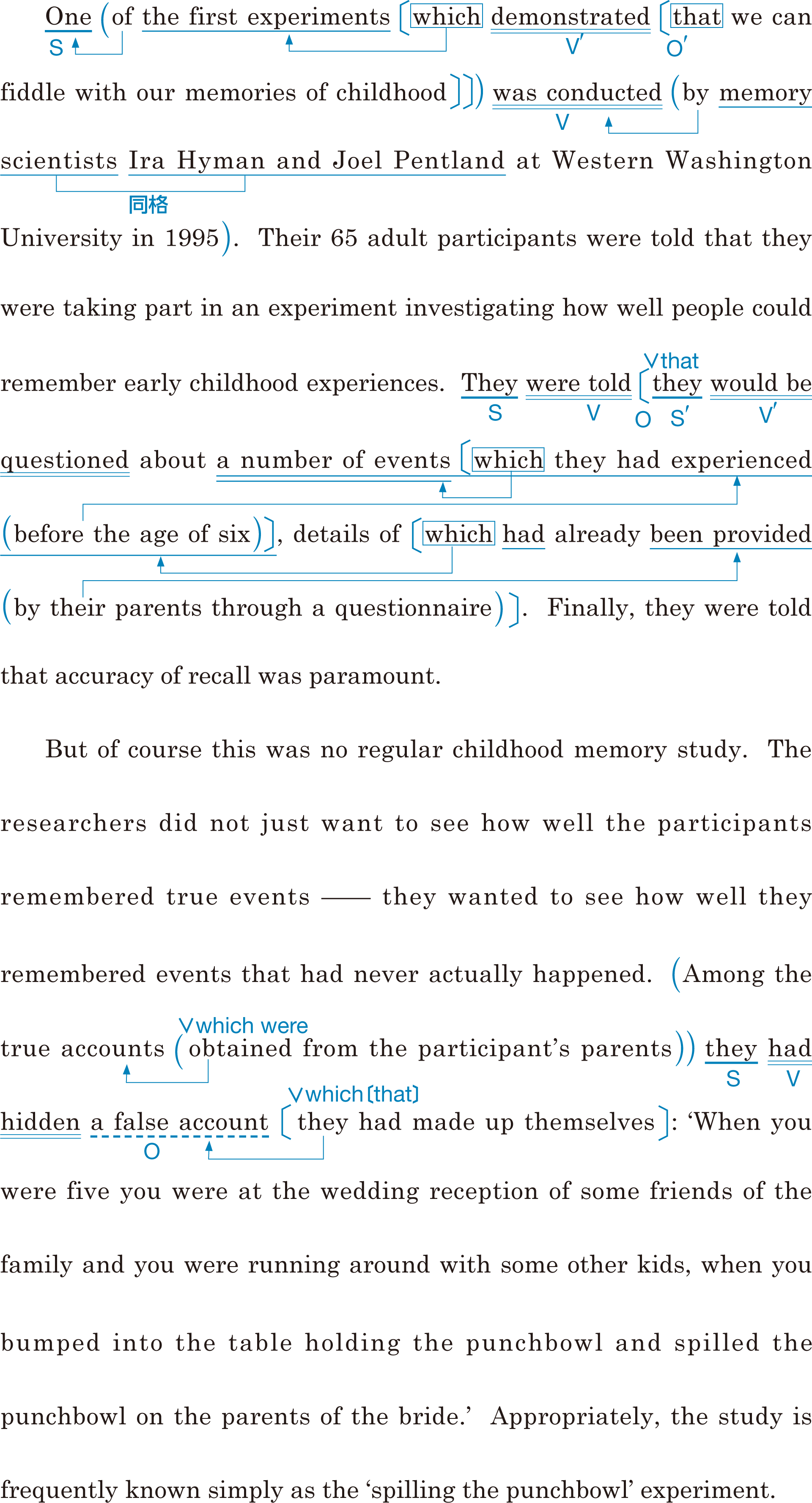

One of the first experiments which demonstrated that we can fiddle with our memories of childhood was conducted by memory scientists Ira Hyman and Joel Pentland at Western Washington University in 1995. Their 65 adult participants were told that they were taking part in an experiment investigating how well people could remember early childhood experiences. They were told they would be questioned about a number of events which they had experienced before the age of six, details of which had already been provided by their parents through a questionnaire. Finally, they were told that accuracy of recall was paramount.

But of course this was no regular childhood memory study. The researchers did not just want to see how well the participants remembered true events —— they wanted to see how well they remembered events that had never actually happened. Among the true accounts obtained from the participant’s parents they had hidden a false account they had made up themselves: ‘When you were five you were at the wedding reception of some friends of the family and you were running around with some other kids, when you bumped into the table holding the punchbowl and spilled the punchbowl on the parents of the bride.’ Appropriately, the study is frequently known simply as the ‘spilling the punchbowl’ experiment.

私たちが自分たちの子ども時代の記憶を操作することができるということを証明した最初の実験の1つが,1995年にウエスタン・ワシントン大学の記憶科学者のアイラ・ハイマンとジョエル・ペントランドによって行われました。65人の成人の被験者は,人が幼年期の経験をどのくらいよく覚えているかを調査する実験に参加していると告げられました。また,アンケートによって彼らの親から詳細をすでに聞き出していた,6歳以前に経験したいくつかの出来事について質問されるでしょうと伝えられました。最後に,記憶の正確さが最も重要だと言われました。

しかしもちろんこれは子供時代の記憶の普通の研究ではありませんでした。研究者たちは被験者たちが本当にあった出来事をどのくらいよく覚えているかを知りたかっただけではなく,実際には決して起こらなかった出来事をどのくらいよく覚えているかを知りたかったのです。被験者の親たちから得た本当の話の中に研究者たちが自分たちで作ったにせの話を忍ばせました。それは「あなたが5歳の時に家族の友人の結婚披露宴に出席していて,あなたは何人かの他の子どもたちと走り回り,パンチボウルが置いてあったテーブルにぶつかり,花嫁の両親にパンチボウルをひっくり返した」というものでした。これにふさわしく,この研究はしばしば単に「パンチボウルをひっくり返す」実験として知られています。

Q1 What was the purpose of the spilling the punchbowl experiment?

- fiddle いじる

- Ira アイラ

- Hyman ハイマン

- Joel ジョエル

- Pentland ペントランド

- Western Washington University ウェスタンワシントン大学

- questionnaire アンケート

- paramount 最重要の

- obtain(ed) ~を得る

- reception 宴会

- punchbowl パンチボウル(パーティーなどで飲み物を入れる大きな器)

- bride 花嫁

Section5

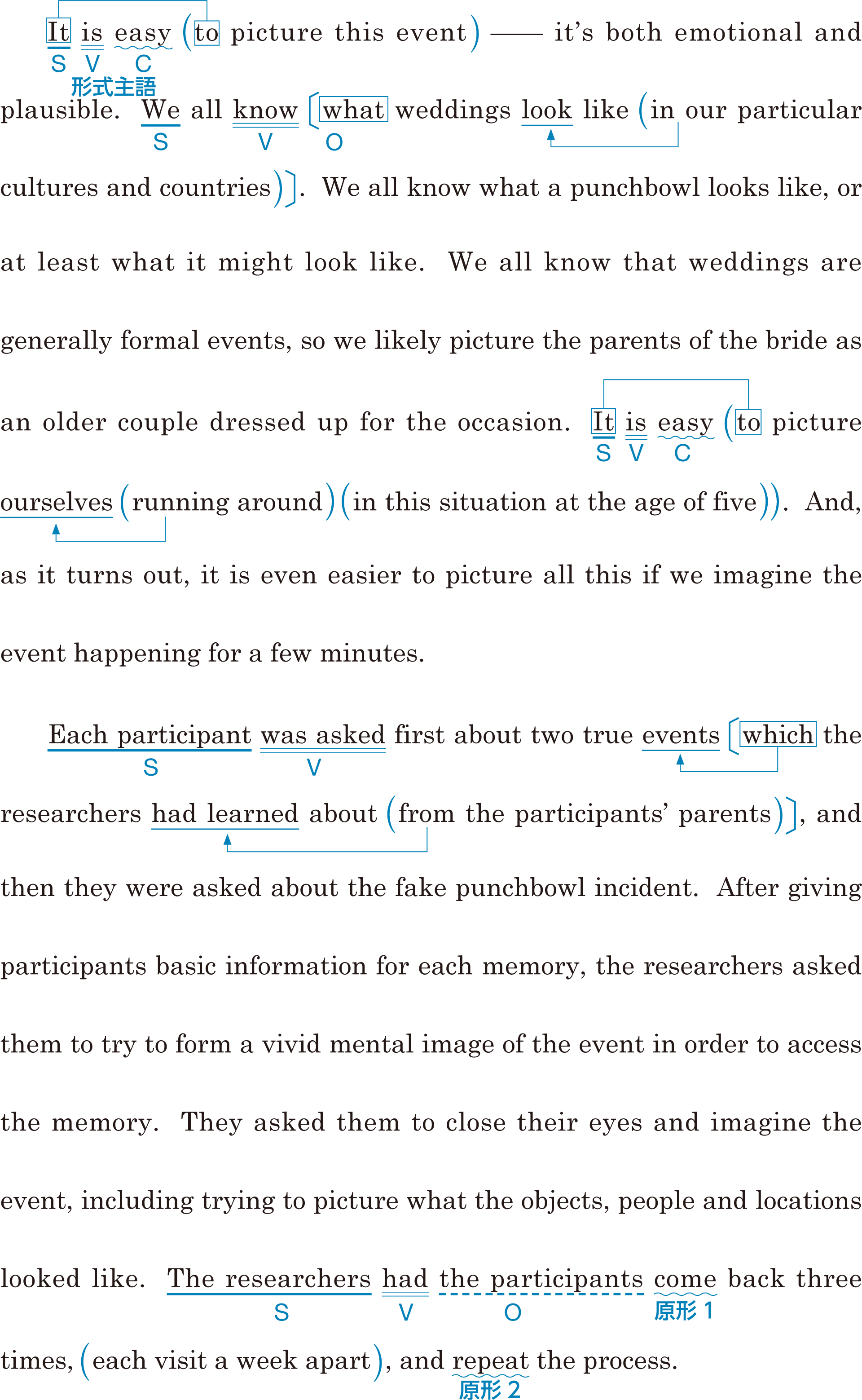

It is easy to picture this event —— it’s both emotional and plausible. We all know what weddings look like in our particular cultures and countries. We all know what a punchbowl looks like, or at least what it might look like. We all know that weddings are generally formal events, so we likely picture the parents of the bride as an older couple dressed up for the occasion. It is easy to picture ourselves running around in this situation at the age of five. And, as it turns out, it is even easier to picture all this if we imagine the event happening for a few minutes.

Each participant was asked first about two true events which the researchers had learned about from the participants’ parents, and then they were asked about the fake punchbowl incident. After giving participants basic information for each memory, the researchers asked them to try to form a vivid mental image of the event in order to access the memory. They asked them to close their eyes and imagine the event, including trying to picture what the objects, people and locations looked like. The researchers had the participants come back three times, each visit a week apart, and repeat the process.

この出来事をイメージすることは簡単です。なぜならそれは感情に訴える,いかにもありそうなことだからです。私たちはみな,自分の個々の文化や国における結婚披露宴がどのようなものであるか知っています。私たちはみな,パンチボウルがどのようなものか,少なくともこういうものだろうということを知っています。私たちはみな,結婚披露宴はたいていフォーマルなものであることを知っているので,花嫁の両親がこの儀式のために盛装している年配の夫婦であることをたぶんイメージするでしょう。この状況で5歳の自分が走り回っていることをイメージすることも簡単です。結局のところ,その出来事が起こるのを数分間想像すると,この全体をイメージすることはもっと簡単でさえあります。

それぞれの被験者は最初に,研究者が彼らの両親から聞いていた2つの実際にあった出来事について質問され,それからにせのパンチボウルの事件について尋ねられました。研究者は被験者にそれぞれの記憶の基本的な情報を与えたのち,記憶にアクセスするためにその出来事を鮮明に心に浮かべてみるように求めました。研究者は被験者に,物や人や場所の様子をイメージしてみることも含めて,目を閉じてその出来事を思い浮かべるように求めました。研究者たちは,被験者たちを1週間間隔で3回来させ,この過程を繰り返させました。

Q1 Why does the author say the image of “the spilling the punchbowl” event is easy to picture?

Q2 What were the participants asked to do by the researchers with regard to the fake incident, after they had been given basic information for the memory?

- couple カップル

- fake にせの

- incident 出来事

- vivid はっきりした

- access ~を呼び出す

Section6

What they found will astonish you. Just by repeatedly imagining the event happening, and saying out loud what they were picturing, 25 per cent of participants ended up being classified as having clear false memories of the event. A further 12.5 per cent could elaborate on the information that the experimenters provided, but claimed that they could not remember actually spilling the punch, and were therefore classified as partial rememberers. This means that a large number of people who pictured the event happening thought that it actually did happen after just three short imagination exercises, and that they could remember exactly how it happened. This demonstrates that we can misattribute the source of our childhood memories, thinking that something we imagined actually happened, internalising information that someone suggested to us and spinning it into a part of our personal past. It is an extreme form of confabulation that can be induced by someone else by engaging your imagination.

研究者たちが発見したことを知ればあなたは驚くでしょう。ただ繰り返し出来事が起こっているのを思い浮かばせ,イメージしているものを声に出して言うだけで,被験者の25パーセントがこの出来事のはっきりとした過誤記憶(虚偽の記憶)を持っていると分類されるに至りました。さらに12.5パーセントの被験者は,実験者が与えた情報について詳細に述べることはできましたが,実際にパンチをひっくり返したことは思い出せないと言ったので,彼らは部分的に記憶していると分類されました。このことから,この出来事が起こっているところをイメージした人の多くが,ただ3回の短いイメージトレーニングのあとで,それが実際に起こり,それがどのように起こったかを正確に思い出せると思っていたことがわかります。これは私たちが,想像したものが実際に起きたと考え,誰かが与えてくれた情報を自分のものとして取り入れ,それを自分の過去の一部として作り上げることによって,自分の子どもの頃の記憶の出所を間違う可能性があるということを立証しています。これは他人があなたの想像力を利用することによって誘発される可能性がある作話の極端な形です。

Q1 Why are the results of the experiment astonishing?

- repeatedly 繰り返して

- out loud 声に出して

- per cent パーセント(= percent)《英》

- classify, classified ~を分類する

- experimenter(s) 実験者

- punch パンチ《飲み物》

- partial 部分的な

- internalise, internalising ~を自分のものにする(= internalize)《英》

- spin(ning) 《spin ~ into ...で》~を紡いで…にする

- induce(d) ~を誘発する

- engage, engaging ~を利用する