Disucussion Topic

Q1 Suppose you were the parent of a child under seven years old, what kind of educational opportunity would you give to him?

Q2 What do you think is one way to solve inequality in education?

Section1

In 2011, I met a very poor teenage mother in a slum outside Maputo, the capital of Mozambique (per capita income: less than two dollars a day). She was carrying a baby whom she had given birth to a few weeks before —— inside of her house, with no medical assistance. Of course, the child had no birth certificate, and his mother was unlikely to try to get one —— she could not afford the cost of the bus ride to a registration center. Result: her son is pretty much condemned to a life of poverty. He will never have a property title, be part of a contract, hold a license, join a union, register for college, or vote in an election. Technically, he will not exist. He won’t be alone: it is estimated that two of every three African children do not exist either. They also have no birth certificate.

How come something so apparently trivial that occurs so early in life —— like not having a piece of paper that confirms who you are —— can hurt you so badly and so permanently? Well, it turns out that your chances to succeed in life are quickly spoiled by things that happen long before you arrive in a school, if you ever do. And even if those things don’t happen, it is still not certain that you will make it. Crazy, isn’t it? Welcome to the drama, the frustration, the promise, and the beauty of early childhood development.

2011年,私はモザンビーク(1 人あたりの所得が 1 日 2 ドル未満)の首都マプト郊外のスラム街で,ある非常に貧しいティーンエイジャーの母親に出会いました。彼女は,数週間前に――彼女の家で医療的な助けもなく――産んだ赤ちゃんを抱いていました。もちろん,その子には出生証明書はありませんでしたし,母親がそれを取得しようと努めそうにはありませんでした――彼女には登録センターへ行くバス代を払う余裕もなかったからです。結果,彼女の息子は貧困の一生を送ることをほぼ運命づけられています。彼は資産の所有権を持つことも,契約の当事者になることも,免許を取ることも,組合に加入することも,大学に入学の登録をすることも,選挙で投票することも決してないでしょう。法律的に,彼は存在しないことになるのです。これは彼だけではないでしょう。アフリカの子どもたちの 3 人に 2 人は存在しないことになっていると推定されています。彼らもまた出生証明書を持っていないのです。

なぜ人生のこんなに早い時期に起こる,一見ささいに思えること——あなたが誰であるかを裏づける 1 枚の紙を持っていないというようなことが――そこまでひどく,そしてこんなに永久的に人を傷つける可能性があるのでしょうか。そうです,学校へ通うようになる――もし万が一通うことがあればですが――そのずっと前に起こることによって,人生が成功する可能性は一瞬で台無しにされてしまうということがわかります。そして,そのようなことがたとえ起こらないとしても,成功するかどうかは依然として確かではないのです。ばかげていると思いませんか。幼児期の発達の劇的さ,挫折,将来の有望性,そして美しさにようこそ。

Q1 Why won’t the baby exist technically?

Q2 What will happen in their life if a child doesn’t have a birth certificate?

- teenage 10 代の

- slum スラム街

- Maputo マプト(モザンビークの首都)

- Mozambique モザンビーク

- per capita 1人当たりの

- income 所得

- birth 出生

- give birth to (子)を産む

- assistance 補助

- certificate 証明書

- unlikely ありそうもない

- be unlikely to do …しそうもない

- registration 登録

- pretty much ほとんど

- condemn(ed) ~に運命づける

- poverty 貧困

- property 財産

- union 組合

- register 登録する

- election 選挙

- technically 法的手続き上

- estimate(d) …であると推定する

- African アフリカの

- How come ...? なぜ …

- apparently 見たところ

- trivial ささいな

- confirm(s) ~を裏づける

- permanently 永久に

- make it うまくやる

- crazy 途方もない

- drama 劇的状況

- childhood 幼年時代

Section2

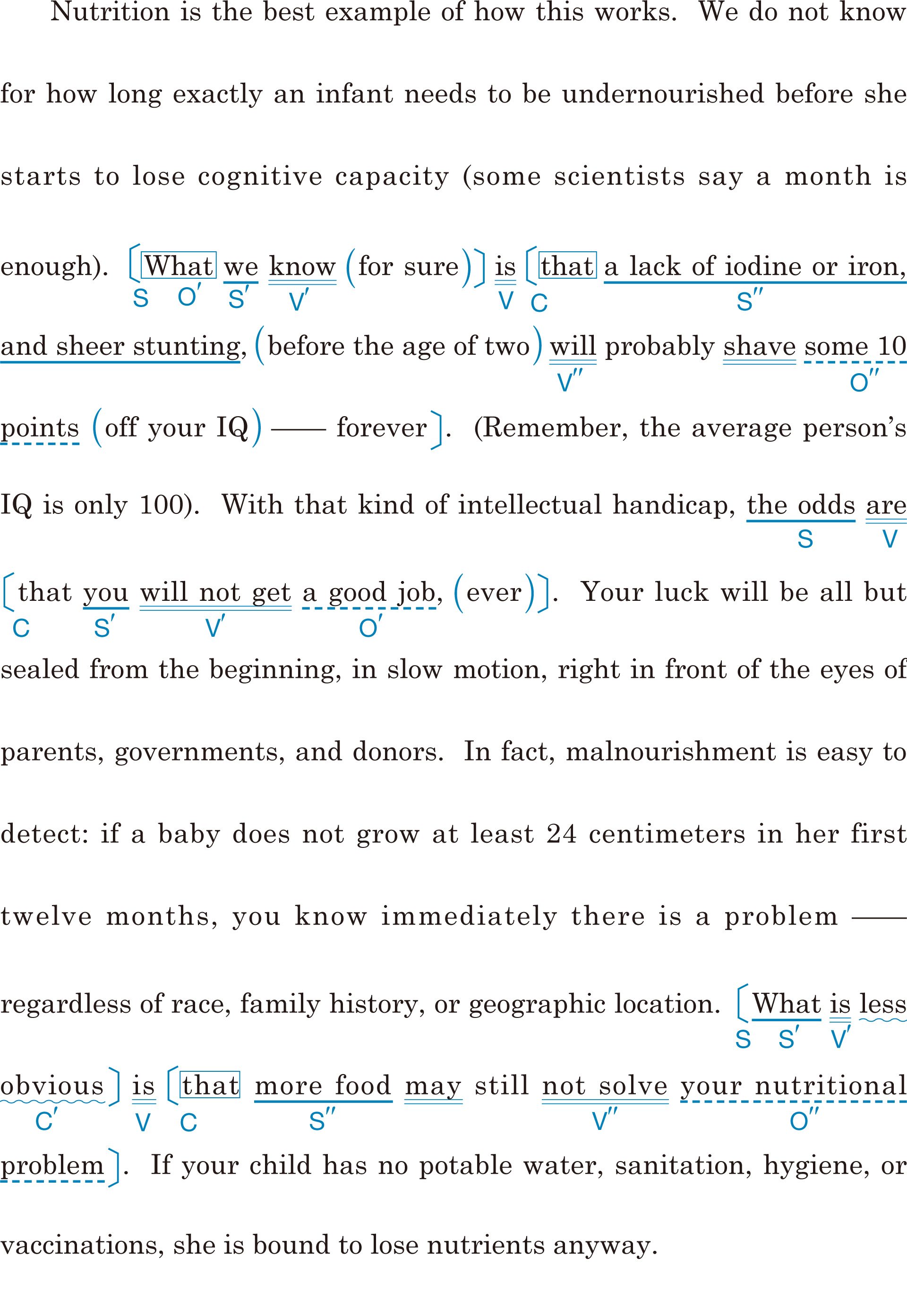

Nutrition is the best example of how this works. We do not know for how long exactly an infant needs to be undernourished before she starts to lose cognitive capacity (some scientists say a month is enough). What we know for sure is that a lack of iodine or iron, and sheer stunting, before the age of two will probably shave some 10 points off your IQ —— forever. (Remember, the average person’s IQ is only 100). With that kind of intellectual handicap, the odds are that you will not get a good job, ever. Your luck will be all but sealed from the beginning, in slow motion, right in front of the eyes of parents, governments, and donors. In fact, malnourishment is easy to detect: if a baby does not grow at least 24 centimeters in her first twelve months, you know immediately there is a problem —— regardless of race, family history, or geographic location. What is less obvious is that more food may still not solve your nutritional problem. If your child has no potable water, sanitation, hygiene, or vaccinations, she is bound to lose nutrients anyway.

栄養摂取は,幼児期の発達がどのように機能するかの最もよい例です。正確にどのくらいの期間幼児が栄養不良の状態が続くと,認知能力を失い始めるのかはわかっていません(1 カ月あれば十分だと言う科学者もいます)。確かにわかっていることは,2 歳になるまでにヨウ素か鉄の不足と明らかな成長阻害があれば,おそらく IQ は10ポイントほど落ちてしまうということです――それも永久にです。(いいですか,平均的な人の IQ は100しかないのです。)そのような知能的なハンディキャップによって,おそらくよい仕事につくことはずっとないでしょう。幸運は最初からゆっくりと,両親や政府や(貧しい人に対して)寄付してくれる人のまさに目の前で封印されたのも同然となるでしょう。実際,栄養失調は発見しやすいものです。もし赤ちゃんが最初の12カ月で少なくとも24センチ背が伸びなければ何か問題があるとすぐにわかります――それは人種,家族歴,地理的な場所には関係はありません。より多くの食べ物を与えても栄養の問題は依然として解決しないかもしれないということはあまり知られていません。子どもに飲料水や衛生設備,衛生的な状態,予防接種が与えられなければ,どのみち栄養は失われていくに違いないのです。

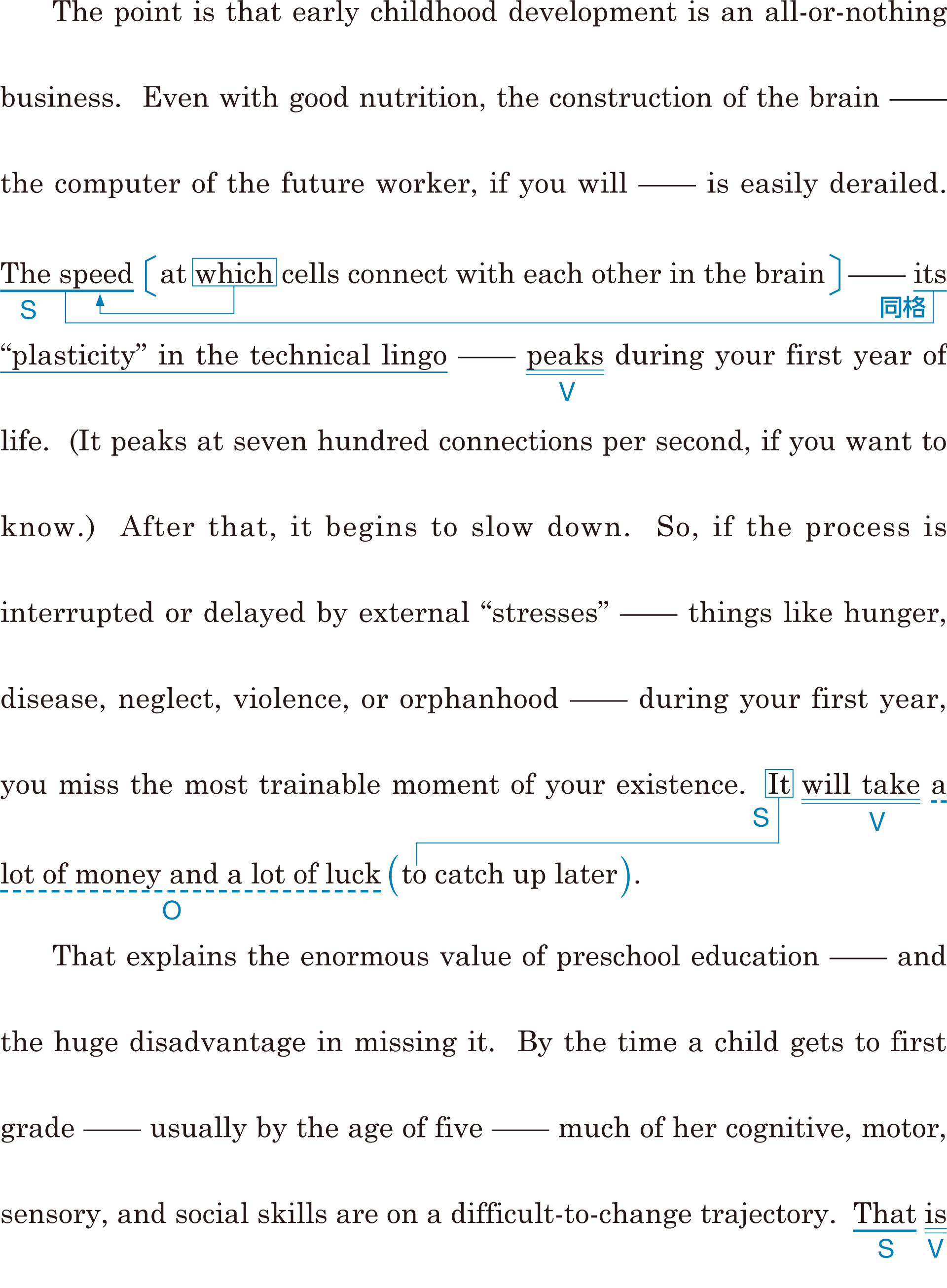

The point is that early childhood development is an all-or-nothing business. Even with good nutrition, the construction of the brain —— the computer of the future worker, if you will —— is easily derailed. The speed at which cells connect with each other in the brain —— its “plasticity” in the technical lingo —— peaks during your first year of life. (It peaks at seven hundred connections per second, if you want to know.) After that, it begins to slow down. So, if the process is interrupted or delayed by external “stresses” —— things like hunger, disease, neglect, violence, or orphanhood —— during your first year, you miss the most trainable moment of your existence. It will take a lot of money and a lot of luck to catch up later.

大事なことは幼児期の発達は妥協を許さない問題であることです。たとえ栄養状態がよいとしても,脳(言うなれば将来〔未来〕の労働者のコンピューター)の形成は,簡単に阻害されます。脳で細胞が相互に結びつく――専門用語では脳の「可塑性」と言いますが――その速さは 1 歳までの間にピークを迎えます。(参考までに,最大で 1 秒間に700回の結合です。)その後,速度は遅くなり始めます。ですから,もしその過程が 1 歳になるまでの間に外的なストレス――つまり飢え,病気,育児放棄,暴力,孤児であることなど――によって阻害されたり,遅らされたりすれば,一生の間で最も教育できる機会を失うことになります。それをあとで取り戻すには多くのお金と多くの幸運が必要でしょう。

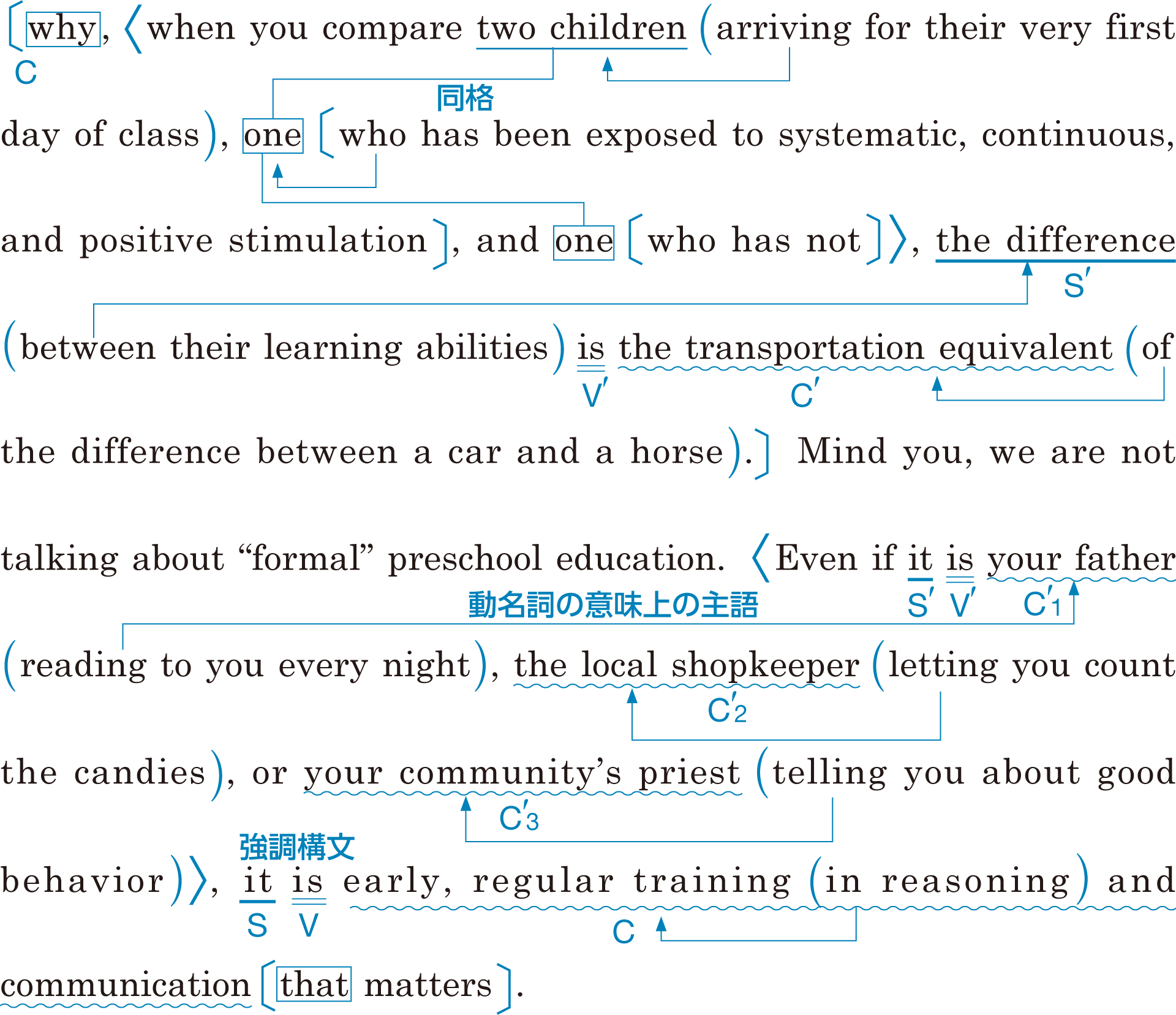

That explains the enormous value of preschool education —— and the huge disadvantage in missing it. By the time a child gets to first grade —— usually by the age of five —— much of her cognitive, motor, sensory, and social skills are on a difficult-to-change trajectory. That is why, when you compare two children arriving for their very first day of class, one who has been exposed to systematic, continuous, and positive stimulation, and one who has not, the difference between their learning abilities is the transportation equivalent of the difference between a car and a horse. Mind you, we are not talking about “formal” preschool education. Even if it is your father reading to you every night, the local shopkeeper letting you count the candies, or your community’s priest telling you about good behavior, it is early, regular training in reasoning and communication that matters.

このことから,就学前の教育に非常に大きな価値があるということ,そしてそれを逃すと大いに不利になるということがわかります。子どもが 1 年生になるまでに――それは普通 5 歳までにということですが――認知的,運動神経的,感覚的,社会的スキルの多くが変えることが難しいコースに入ってしまいます。そういうわけで,その日初めての授業にやってきた 2 人の子ども―― 1 人は体系的な,継続的なそして肯定的な刺激を受けてきた子どもで,もう 1 人はそうでなかった子ども――を比較すると,彼らの学習能力の違いは自動車と馬の輸送能力の違いに匹敵します。いいですか,私たちは「正規の」就学前教育について話しているのではありません。たとえ父親が毎晩読み聞かせをしてくれることだったり,地元のお店の人がキャンディーの数を数えさせてくれることだったり,町の神父が良い行いについて話してくれることだったとしても,大事なのは論理的思考と意思伝達の訓練を早くから,そして普段から行うことなのです。

Q1 What will happen if a child is undernourished before the age of two?

Q2 If brain development is interrupted by external stresses during a child’s first year, what will happen?

Q3 Why is preschool education so important?

- nutrition 栄養摂取

- infant 幼児

- undernourished 栄養不良の

- cognitive 認知的な

- capacity 能力

- iodine ヨウ素

- sheer 完全な

- stunting 成長阻害

- shave ~を減らす

- IQ 知能指数

- intellectual 知的な

- handicap ハンディキャップ

- odds 《the ~で》見込み

- all but ~も同然で

- motion 運動

- donor(s) 寄付をする人

- malnourishment 栄養失調

- detect ~を見つける

- geographic 地理的な

- obvious 明白な

- potable (水が)飲むのに適した

- sanitation 衛生設備

- hygiene 衛生(的な)状態

- vaccination(s) 予防接種

- bound 《be bound to doで》(…する)に違いない

- nutrient(s) 栄養物

- all-or-nothing 妥協を許さない

- if you will 言うなれば

- derail(ed) (計画など)を狂わせる

- cell(s) 細胞

- plasticity 可塑性

- lingo 学術語

- peak(s) 頂点に達する

- interrupt(ed) ~を妨害する

- external 外部の

- hunger 飢え

- neglect 育児放棄

- violence 暴力

- orphanhood 孤児であること

- trainable 教育できる

- existence 生存

- catch up 追いつく

- preschool 就学前の

- education 教育

- motor 運動神経の

- sensory 感覚に関する

- social 社会的な

- trajectory 道筋

- compare ~を比較する

- expose(d) 《expose ~ to ...で》~を…に触れさせる

- systematic 体系的な

- continuous 絶え間ない

- stimulation 刺激

- equivalent 相当するもの

- Mind you. いいかい

- shopkeeper 店主

- candy, candies 砂糖菓子

- priest 聖職者

- regular 規則正しい

- reasoning 論理的思考

Section3

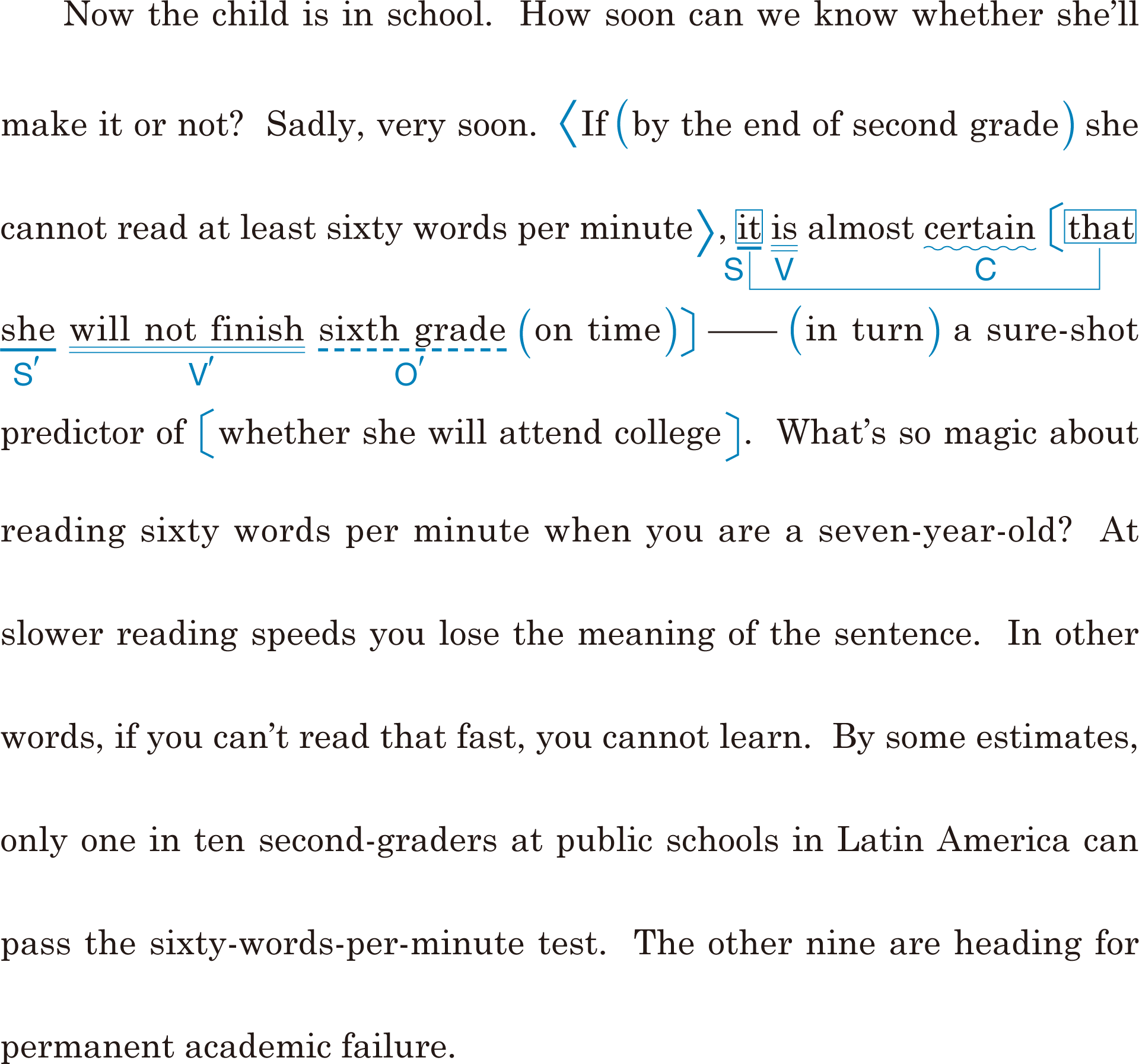

Now the child is in school. How soon can we know whether she’ll make it or not? Sadly, very soon. If by the end of second grade she cannot read at least sixty words per minute, it is almost certain that she will not finish sixth grade on time —— in turn a sure-shot predictor of whether she will attend college. What’s so magic about reading sixty words per minute when you are a seven-year-old? At slower reading speeds you lose the meaning of the sentence. In other words, if you can’t read that fast, you cannot learn. By some estimates, only one in ten second-graders at public schools in Latin America can pass the sixty-words-perminute test. The other nine are heading for permanent academic failure.

さあ,子どもが学校に行き始めます。彼女がうまくやれるかどうか,どのくらいで知ることができるのでしょうか。残念ながら,すぐにわかるのです。もし 2 年生の終わりまでに 1 分間に最低60語の速さで読めなければ,彼女が予定どおりに 6 年生を終えることができないであろうことはほぼ確実です。同様に彼女が大学に行くかどうかも正確に予測できるのです。7 歳の時点で 1 分間に60語読むことの何がそんなに魔法のような力を持っているのでしょうか。それより遅いスピードで読むと文の意味をつかめなくなります。言い換えれば,そのくらいの速さで読めなければ学習できないのです。いくつかの推定によれば,ラテンアメリカの公立学校の 2 年生の10人に 1 人しかこの 1 分間に60語のテストに合格できないと言われています。残りの 9 人は永久に学業不振の道を進むことになります。

Q1 What does a child need to be able to do by the end of second grade if she hopes to attend college?

- in turn 同様に

- sure-shot 正確な

- predictor 予測の判断材料

- Latin America ラテンアメリカ

- permanent 永久的な

Section4

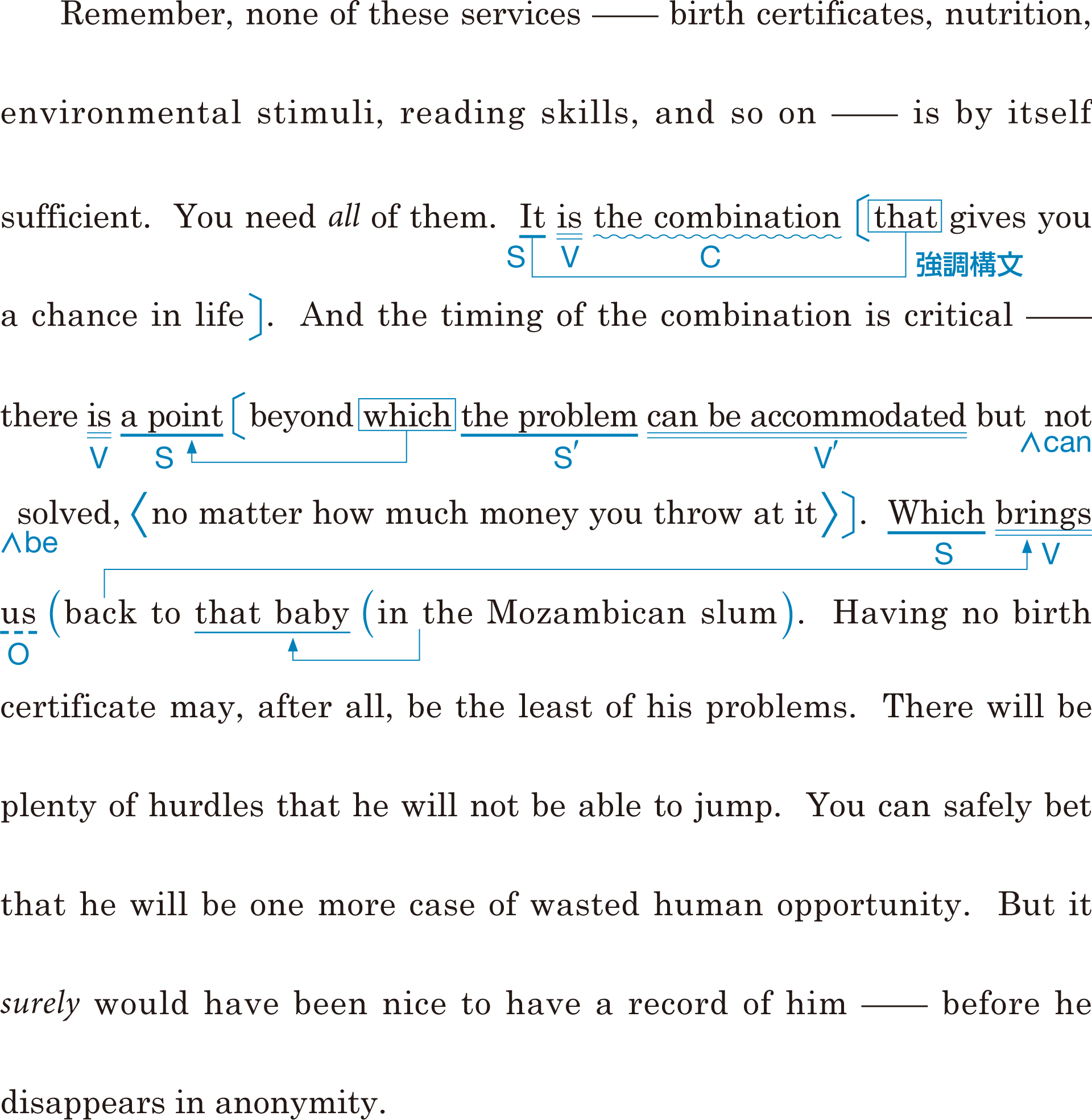

Remember, none of these services —— birth certificates, nutrition, environmental stimuli, reading skills, and so on —— is by itself sufficient. You need all of them. It is the combination that gives you a chance in life. And the timing of the combination is critical —— there is a point beyond which the problem can be accommodated but not solved, no matter how much money you throw at it. Which brings us back to that baby in the Mozambican slum. Having no birth certificate may, after all, be the least of his problems. There will be plenty of hurdles that he will not be able to jump. You can safely bet that he will be one more case of wasted human opportunity. But it surely would have been nice to have a record of him —— before he disappears in anonymity.

いいですか,これらの助け,つまり出生証明書,栄養摂取,環境刺激,読解力などは,どれもそれ 1 つでは十分ではないのです。それらの「すべて」が必要なのです。あなたの人生に可能性を与えるのはそれらを兼ね備えることです。そしてそれらを兼ね備えるタイミングが重要なのです。どんなにたくさんお金をかけても,そこを越えると問題の対応はできても解決はできないという時点が存在するのです。そしてこのことは私たちにモザンビークのスラム街のあの赤ちゃんを思い出させるでしょう。出生証明書を持っていないことは,所詮,彼の抱える問題の中で最も小さい問題かもしれません。彼が飛び越えることのできないたくさんのハードルがこれからあることでしょう。彼が,人間が持っている機会が無駄にされてしまったもう 1 つの事例になるということが確実に断言できます。しかし,彼が名前もないまま消えていく前に彼の記録を残していればよかったということは間違いないでしょう。

Q1 What factors does a child need if he is to have a chance to succeed in life?

- service(s) 助け

- stimuli(<stimulus 刺激)

- timing タイミング

- critical 不可欠な

- accommodate(d) ~に対応する

- no matter how どんなに…であっても

- Mozambican モザンビークの

- hurdle(s) ハードル

- bet …だと断言する

- anonymity 氏名不詳